This article was written by Samantha Hardy and Danielle Hutchinson, with significant contributions from Dan Berstein.

Why adapt your practice?

As I’ve discussed in a previous article, one size does not fit all. We live in a diverse world and we work with a diverse client base. We can do so much more to be inclusive in our practice than simply screening out those who don’t fit with what we do, or making tokenistic adjustments.

Having said this, you don’t need to be everything for everyone. It’s important to know what is negotiable and what is not for you in your practice. For example, as a mediator you may not be willing to give (and may have regulations that prevent you from giving) advice to people in your process. However, be open minded, you may have more room for flexibility than you realise.

The good news is that we know the broader DR community is interested in exploring what it means to provide genuinely inclusive and accessible practices. For example, in the recent review of Australia’s mediator accreditation system (the NMAS Review) Australian mediators recognised that, like many other industries, they had an increasing awareness of the importance of diversity and inclusion and despite good intentions, some attempts to account for diversity and inclusion were ill-conceived or inappropriate.

In response, recommendations arising out of the NMAS Review proposed revisions to the system, including:

Embed diversity and inclusion into the objectives of the revised system;

Provide guidance on implementing a contextualised and intersectional approach;

Articulate expectations and provide illustrations of practice within the revised professional practice standards, such as advanced practitioners drawing on the principles of universal design to evaluate the extent to which services are accessible and inclusive.

The Mediator Standards Board (MSB) is still in the process of finalising the revised system, AMDRAS, so it remains to be seen whether the MSB will heed this call and seize this opportunity to cement their footprint as global thought leaders in the advancement of mediator practice.

In the meantime, we hope that this article might offer a little hope to those practitioners who continue to feel daunted and overwhelmed as they grapple with how to approach making adaptations to their practice.

What’s the best approach for practitioners?

While there are various approaches available to practitioners, we will focus on two of the most effective ways to enhance your capacity to offer flexibility and support to clients with varying needs. One approach, which typically takes more time and effort, is co-design or participatory design. This involves working with clients at the outset to design a bespoke process that best meets their needs. While this approach has many long-term benefits, and is often perceived as the gold standard of service design, it has limitations. For example, not all clients (or practitioners) have the time or the resources to engage in this kind of process design.

The other, often simpler, approach is for the practitioner to have a process based on the principles of universal design. This can start with the practitioner developing a list of sample adaptations and variations designed to support clients to participate, and that, as a matter of course, are universally available to clients.

(1) Co-Design or Participatory Design

Co-design or participatory design is when we actively involve all stakeholders in the design process to help ensure the result meets their needs and is usable. This brings together lived and professional experience. It is a working “with”, collaborative process design. This kind of design process is often required in big multi-party stakeholder situations but can be used even in small two-party conflicts. To do this properly, however, the practitioner needs considerable knowledge and skills to ensure that the process of co-design is managed appropriately, and that the process designed is fit for purpose.

The basic steps are:

The practitioner identifies which elements of their practice are up for negotiation and which are not.

Stakeholders are informed of the co-design opportunity.

Stakeholders are engaged and aligned in that task.

Consultation takes place with relevant stakeholders about their process needs and ideas.

Stakeholders imagine and discuss different possibilities, and decide on a process.

The process is created and implemented.

Afterwards, the process is jointly evaluated for future learning.

There is an important distinction between offering effective co-design, or simply seeking input for the purpose of considering reasonable adjustments. The key to the distinction is the nature and level of influence, including where the decision-making power resides. While consultation is typically an important form of engagement and information gathering, more is required for a process to constitute co-design.

(2) Adapting your process

If co-design is not something that fits with your current client base, market, and business model, another option is to offer adaptations to your process to make it more inclusive.

Firstly, ensure that your base process is inherently flexible

Start with the principles of universal design. While originally a concept applied to architecture, it can be applied equally to what we do in designing a mediation process. It means, effectively, designing a process that is inherently flexible in accommodating the needs of people with diverse abilities, so that these people can feel that they belong instead of needing to ask for special treatment.

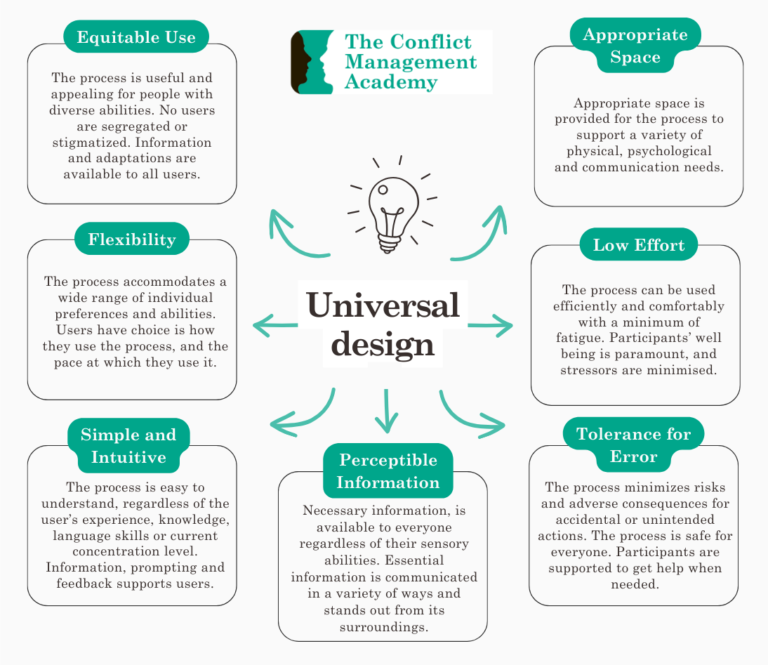

Dan Berstein, an expert on mental health and conflict, explains in Chapter 8 of his book Mental Health and Conflicts, that taking this approach not only benefits people who live with disabilities, but also everyone potentially benefits from the enhanced design. Dan offers his unique and detailed insight into the seven key universal design principles: equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low effort, and appropriate space, and shows practitioners how they can be applied across a variety of contexts, including dispute resolution.

For example, in building design, wider doorways make it possible for someone with a wheelchair to enter a building easily without assistance, while at the same time making it easier for someone who does not have a disability but is carrying groceries or moving furniture. An example for dispute resolution practitioners, is when you adapat your practice to include online options, this supports people who are unable to access a physical mediation room, but also provides opportunities for those in rural areas or who prefer the convenience of participating from a location of their choice. Online options also feel safer and more comfortable for some individuals, who may not want to always share their reasoning for opting for a virtual session.

Secondly, adapt based on individual clients’ requests (not assumed needs)

Despite goodwill and good intentions, practitioners can fall into two common adaptation traps. They tend to get stuck with the worry that they do not know what kinds of adaptations are appropriate for which clients. Conversely, they make uninformed assumptions about what particular people might need.

Both of these problems can be easily avoided by simply asking everyone you work with what would be helpful for them, irrespective of whether or not you think they might need adjustments to participate. The great thing about doing this is that you avoid the risk of inadvertent discrimination resulting from making assumptions about people’s needs, and you also offer everyone the opportunity to tell you what would help them to make the most out of the experience. With that said, it’s important to keep in mind that no one is required to disclose anything about their needs if they don’t want to. People with disabilities have a variety of reasons why they might decide not to seek adjustments, preferring instead to keep any needs private.

While it might seem counterintuitive, you do not actually need to know or ask for the reasons underlying a request. This is important because many practitioners don’t realise that expecting a client to explain or justify requests can inadvertently pressure or force a client to disclose their diagnosis. Many clients may not be willing or able to disclose their needs to you. This is good news for practitioners as it removes any pressure for you to have all the answers and, instead, recognises that your clients know what they need. You only need to give people the opportunity to request adaptations if they wish to do so, and then discuss what options might be available to them.

This might require a shift in mindset for many practitioners. It’s only human for some people to fear that they will be bombarded with multiple or unreasonable requests or that they will lose control over their process. While practitioners are entitled to have their own boundaries about what they are and are not willing to vary, when faced with such requests, it is our professional obligation to challenge these fears, assumptions, and discomforts, and think critically about what it might take for us to overcome any barriers or obstacles to making the adjustments.

Of course, you don’t need to change everything. But sometimes, even small adaptations have a big impact, particularly where there is a risk that an accumulation of stressors might reduce a person’s capacity to participate. Sometimes a few small adaptations are enough to get people through the process without major challenges. Other times, people may require multiple changes. The key is to talk to your client and to negotiate these changes on a case-by-case basis.

It is also vital that this does not devolve into a process of checking boxes at intake. The answer lies in genuine openness to flexibility and commitment to asking your clients what would help them.

It’s also immensely helpful to have a suite of suggestions available, as some clients may not know what kinds of flexibilities are available to them. In his book Mental Health and Conflicts, Dan Berstein provides the following helpful script to bring this up with clients:

“My usual process is ….. but I’m open to suggestions about how we can adapt this to make you most comfortable and best able to participate in a way that works for you and everyone else involved. Some areas in which we could negotiate adaptations include…..”

What next?

Areas in which process adaptations and flexibility might be possible and helpful to your clients include:

How, when and to whom communication takes place;

How, when and to whom information is provided;

The space in which the process is conducted (physical or virtual, and variations within each);

Timing of the process or steps within the process;

Topics covered in the process;

Who is involved, and in what ways;

Which process steps are included, in what order;

How the process is ended and by whom;

What happens is someone is unhappy with how things are going, or needs help.

Would you like a list of sample adaptations?

We are currently compiling a list of suggested adaptations / flexibilities that practitioners could share with clients as a prompt for thinking about what would help them participate in a process. Please get in touch if you’d like a copy of this, and/or if you have ideas of things we could add to it.

Samantha Hardy, Adapting our box: Co-designing a conflict resolution process.

https://conflictmanagementacademy.com/adapting-our-box-co-designing-a-conflict-resolution-process/

Dan Berstein, Mental Health and Conflicts: A Handbook for Empowerment (2022) ABA Section of Dispute Resolution, https://www.americanbar.org/products/inv/book/420367133/

Mediator Standards Board, The NMAS Review, https://msb.org.au/nmas-review

Mediator Standards Board, Draft AMDRAS, https://msb.org.au/themes/msb/assets/documents/DRAFT%20AMDRAS%20Standards%20V1%20with%20Appendices%201-4.pdf

Centre for Excellence in Universal Design, The 7 Principles, https://universaldesign.ie/about-universal-design/the-7-principles

What adaptations have you offered clients in the past?

What led you to offer those adaptations?

Do you offer flexibility and adaptation to all clients? If so, how? If not, why not?

What areas of flexibility do you have in your practice?

How could you be more adaptive to diverse clients’ needs?

How could you ensure clients know about the potential for flexibility in your practice?

I’d love to hear from you all about things you have used in the past, or been asked to do in the past, to support your clients.