By Samantha Hardy and Claire Holland

Mediators play a crucial role in helping parties resolve disputes, but can they actually provide advice? The answer is more nuanced than it may initially appear. In Australia, mediation is predominantly a facilitative process, meaning mediators do not make decisions for the parties. However, there are circumstances where a mediator may offer advice, provided specific conditions are met.

This article explores when and how advice may be given, the different styles of mediation that influence this practice, and the risks and ethical considerations that mediators must keep in mind.

The role of a mediator in Australia

According to the Australian Mediator and Dispute Resolver Accreditation Standards (AMDRAS), mediation is:

“A confidential facilitative process, in which the parties to a dispute, with the help of a dispute resolution practitioner (the mediator), endeavour to reach decisions and/or agreements. The mediator does not have a determinative role and does not advise the parties unless with their express consent.”

The key point here is that a mediator does not have a determinative role—meaning they do not impose decisions or direct outcomes. Unlike a judge, arbitrator, or even a conciliator in certain circumstances, a mediator is there to guide discussions, not to determine what is fair or to recommend specific outcomes.

This facilitative role, however, does not entirely prohibit mediators from sharing knowledge. The extent to which they can do so depends on the context of the mediation and the expectations set by the parties and the mediation service.

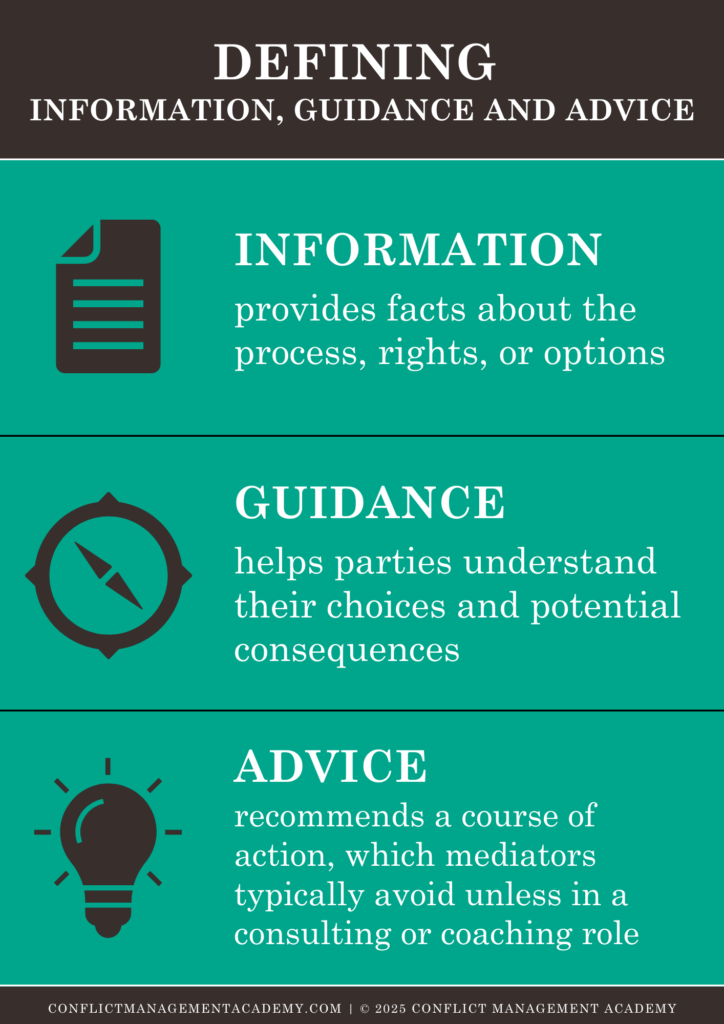

Defining information, guidance and advice

To understand the limitations on providing advice, it is essential to define what constitutes ‘advice’ in mediation. AMDRAS refers to information, guidance and advice.

Here’s how we define and compare these three concepts:

Providing Information – The mediator or conflict resolution practitioner shares neutral, factual details without interpretation or recommendation. This empowers parties to make informed choices on their own. For example, a mediator might say, “In today’s mediation, you will both have an opportunity to speak and listen to the other party. Today’s process is also confidential, to the extent we discussed in the intake and as outlined in your agreements to mediate.” The key traits here is that the information provided is objective, fact-based, and there is no personal input.

Providing Guidance – The mediator helps parties understand their options by explaining possible outcomes, providing process guidance, or explaining approaches, without making a specific recommendation. Guidance clarifies choices but leaves the decision to the parties. For example, a mediator could state, “Some people find it helpful to start with their main concerns, while others prefer to first acknowledge the other person’s perspective. Either approach can help build a constructive conversation.” The key trait demonstrated in providing guidance is that the mediator frames information to help parties navigate their decisions but still remains neutral.

Providing Advice – The mediator steps into a more directive role by recommending a specific course of action based on their expertise. While some mediation models discourage this, other conflict resolution roles (such as coaching or consulting) may involve advice-giving. For example, a mediator could make a specific process or outcome recommendation, such as saying to one party, “I recommend that you begin by acknowledging the impact of the conflict on the other party, as that may reduce their defensiveness and lead to a more productive dialogue.” The key trait here is that the mediator is acting on their knowledge or experience and making statements that the parties may rely on.

The key differences across these definitions in the mediation context are:

Information provides facts about the process, rights, or options.

Guidance helps parties understand their choices and potential consequences.

Advice recommends a course of action, which mediators typically avoid unless in a consulting or coaching role.

What kinds of information, guidance and advice can mediators provide?

Under 6.1.1 (g) Domain 1 – Professional knowledge, AMDRAS states that practitioners must understand the scope and types of information, guidance or advice offered by non-determinative dispute practitioners. Examples given of things that fall within the scope of appropriate sharing by the mediator include providing information, guidance and advice about:

The cultural, psychological or social context applicable (e.g. to avoiding scheduling a mediation during a religious festival, and guidance on the inclusion of young people);

Procedural matters, including the process if no agreement is reached (e.g. what to expect from the facilitative mediation process, the role of the mediator, at what stage the parties can suggest options for resolution, the process if the parties don’t attend, etc.)

Examples of substance, merits, options and outcome-based information, guidance or advice (e.g. information about common topics for the agenda as part of intake or during the agenda setting stage, indirect guidance via reality testing in private sessions, suggesting further options, etc.)

Under 6.1.2(h) Domain 2 – Professional skills, AMDRAS specifically permits practitioners providing information, guidance and advice as appropriate, including through the use of reality testing. (See below for the full text of this section and relevant sections from the AMDRAS Code of Ethics).

When Can a Mediator Provide Advice?

To summarise, under AMDRAS, a mediator may provide advice only if the following five conditions are met:

Expertise in the Subject Matter – The mediator must have the necessary knowledge and experience to provide informed advice.

Explicit Consent from Both Parties – The parties must agree that advice will be permitted within the mediation.

Permitted by the Mediation Service – Some mediation services strictly prohibit giving advice, while others allow for some discretion.

Accreditation Level – The mediator’s qualifications and accreditation level may determine whether they are permitted to offer advice.

Professional Indemnity Insurance – A mediator providing advice must have coverage to protect against potential liability arising from incorrect or harmful guidance.

Even if all conditions are met, the mediator must carefully consider whether providing advice is appropriate in the given context.

Therefore, generally speaking:

Providing general information is permitted. For example: “In mediation, parties must disclose all financial assets.” This is factual and does not influence decision-making.

Giving a recommendation or opinion on an outcome is generally not permitted. For instance: “You should agree to a 60:40 property split—it’s the best deal you’ll get.” This crosses the line into advisory territory, which is not appropriate in a facilitative mediation setting. A mediator can explain the mediation process, outline general legal principles, and discuss common outcomes in similar cases. However, they must refrain from directing parties toward a particular settlement.

Different Mediation Styles and Their Approach to Advice

Not all mediation follows a purely facilitative approach. Different styles of mediation impact the extent to which a mediator may provide advice:

Facilitative Mediation – Advice is not given unless explicitly agreed upon. This is the most common approach in Australia.

Evaluative Mediation – The mediator may offer opinions on legal or financial matters, typically used when parties seek a structured assessment.

Transformative Mediation – Advice is not given as the process focuses on party empowerment and improving communication.

Advisory Mediation – The mediator provides structured guidance, which may include advice, though this style is less common.

The context of the dispute also plays a role. In family dispute resolution, facilitators who are also accredited Family Dispute Resolution Practitioners (FDRPs) may have broader scope to provide insights related to family law. In commercial disputes, parties may expect some level of guidance from the mediator, whereas in workplace disputes, advice is generally avoided.

Ethical Considerations and Risks of Giving Advice

Even when advice is technically permissible, mediators must consider the ethical implications and potential risks:

Risk of Bias – Any advice given may be perceived as favoring one party over the other, undermining the mediator’s neutrality.

Legal Liability – If a party acts on the advice and suffers a negative outcome, the mediator may be held accountable.

Loss of Neutrality – The primary role of a mediator is to facilitate discussions rather than direct outcomes. Providing advice could shift their perceived role from neutral facilitator to decision-maker, compromising trust in the process.

Best Practices for Mediators

For new mediators in Australia, it is critical to maintain professional integrity and adhere to ethical guidelines. The following best practices can help ensure compliance:

Know Your Accreditation Standards – Always check AMDRAS and professional accreditation rules regarding advice.

Clarify Boundaries from the Outset – Clearly outline whether advice will be given as part of the mediation agreement.

Use Cautious Language – If sharing knowledge, ensure it is presented as neutral information rather than a recommendation.

Seek Further Training – If engaging in evaluative or advisory mediation, undertake additional training to meet competency standards.

Document Consent – If advice is to be provided, obtain written agreement from both parties to prevent disputes about the mediator’s role later on.

Conclusion

Mediators generally do not provide advice unless specific conditions are met. Facilitative mediation—the dominant model in Australia—focuses on guiding discussions rather than influencing decisions. While other mediation styles allow for varying levels of advice, mediators must weigh the ethical considerations and risks carefully.

For those practicing or considering mediation as a profession, a thorough understanding of AMDRAS standards and professional accreditation requirements is essential. Mediation is about empowering parties to find their own solutions, not making decisions for them.

By maintaining clear boundaries and upholding ethical standards, mediators can ensure they provide effective and professional dispute resolution services while preserving the integrity of the mediation process.

EXTRACTS FROM AMDRAS

Under 6.1.2(h) Domain 2 – Professional skills, AMDRAS specifically permits practitioners providing information, guidance and advice as appropriate, including through the use of reality testing. AMDRAS states that: