Mediation is often described as a confidential process, however confidentiality is not straightforward and there are many variations and exceptions to the principle of confidentiality in mediation. These variations may depend on what the mediator and the parties agree on, which model of mediation the mediator offers (e.g. facilitative, transformative, narrative), the substance of the conflict (e.g. whether it relates to matters covered by family law), the location (e.g. different states of Australia have different laws about what kinds of things need to be reported to authorities), and context in which the mediation takes place (e.g. whether or not it is a court-connected process related to existing litigation, within an organisation with relevant policies and procedures, or a community conflict between two neighbours who have a personality clash).

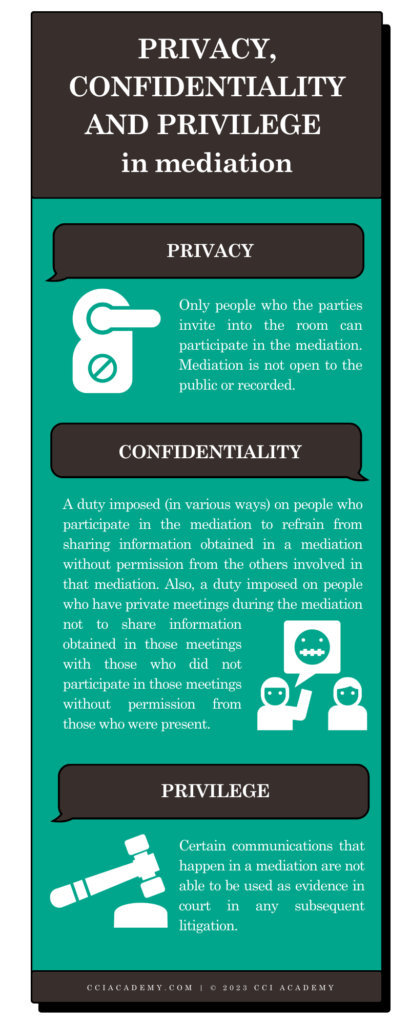

Confidentiality, privacy and privilege

As Bobette Wolski points out in her 2020 extensive review of confidentiality, privacy and privilege in mediation in Australia, these things are quite different, although they may intersect in various circumstances. Here is a broad overview of the difference between these three concepts:

The concept of privacy is relatively uncontroversial. People involved in mediation usually understand that they can’t bring anyone along to watch what happens or live stream the mediation on YouTube! Although, in theory, if everyone agrees that this is acceptable, there is no reason this could not happen. You never know, it could be the next big thing in reality television!

Privilege is quite a complicated legal concept that determines if, and when, information shared in a mediation can be used as evidence in court. Usually when it’s relevant (when litigation is pending) there are lawyers involved to advise on this aspect of the process.

The most challenging area is that of confidentiality. Many mediators simply inform their parties that mediation is confidential except in exceptional circumstances in which the law might require disclosure (e.g. a serious crime has been committed or there’s a significant risk of harm). However, this is a gross oversimplification of how confidentiality works, and does not provide participants with some choices that are actually available to them in relation to how they might manage confidentiality in their particular mediation.

To whom does / could confidentiality apply?

It’s important to recognise that different confidentiality obligations may apply to the mediator, the parties to the conflict, and their support people or legal representatives. Administrative staff involved in organising or managing records of a mediation are also people who should be considered as people who may have obligations to keep certain information confidential.

The mediator

The requirement that the mediator uphold confidentiality is often seen as an ethical obligation. This is reinforced by the Australian National Mediation Practice Standards. Section 10(1)(c)(vii) describes as an ethical principle of mediation “confidentiality privacy and reporting obligations”. Section 9 requires mediators (and their administrative staff) not to disclose any information obtained during mediation, including any notes and records of the mediation, except:

- With consent of participant to whom the confidentiality is owed;

- Where non-identifying information is required for legitimate research, supervisory or educational purposes;

- When required to do so otherwise by law;

- Where permitted to do so otherwise by ethical guidelines or obligations;

- Where reasonably considered necessary to do otherwise to prevent an actual or potential threat to human life or safety.

The parties

Confidentiality by the parties is usually covered by an agreement between them. There is considerable scope for what the parties might choose to agree on, including no confidentiality at all, confidentiality with some exceptions, or blanket confidentiality over all discussions.

Any other people present (e.g. lawyers / support people)

The parties can decide whether and what should be kept confidential by any other participants in the mediation, but this needs to be covered by an express agreement with those participants.

Administrative staff

Often overlooked when considering confidentiality are administrative staff, from the receptionist at the mediation venue, to the assistant responsible for scheduling the mediation, filing records and sending invoices. While these staff probably do not have an in depth knowledge of the content of discussions in mediation, they know enough to be potentially problematic if shared. For example, imagine a receptionist at the pub on a Friday night saying to their mates “you’ll never guess who came in for a mediation today”!

What could be confidential?

It’s also important to determine exactly what the parties want to keep confidential. This could include: that the mediation has taken place, commercial in confidence information disclosed during the mediation, documents shared or prepared during the mediation, words said by a participant during the mediation, and/or the outcome of the mediation. It is possible that there could be different confidentiality expectations about each of these things. For example, the parties might be comfortable with people knowing the mediation has taken place (in a workplace context, chances are quite a few people already know this), but do not want specific details of what was said in the mediation shared with anyone. They may also be willing to agree that any written agreement made can be shared with a direct line manager and/or the human resources staff, but no further.

Why is confidentiality a good idea?

Without confidentiality, parties may not be comfortable sharing sensitive information with each other. Confidentiality, at least in theory, creates an environment that promotes trust, so that parties feel free to openly discuss issues relating the conflict. This can be particularly important if a party makes an admission or acknowledges a contribution to the conflict that they would prefer others not to know about.

When the mediator meets with a party separately during the mediation, that party is more likely to honestly discuss their needs and concerns with the mediator if they believe that the mediator will not share that information with the other party when they return to joint session.

What are some challenges with confidentiality?

Enforcing confidentiality can be very difficult – it is hard to prevent someone from talking about what happened in a mediation. In a workplace situation, a breach of confidentiality could be seen as a breach of the organisation’s code of conduct and the party making a disclosure could potentially be sanctioned or warned as a consequence. However, it can be hard to find the line between an understandable or permissible disclosure (e.g to someone within a party’s “legitimate field of intimacy’) and one that is explicitly inappropriate (e.g. someone posting on social media a direct quote made by a person in the mediation).

In many situations, when someone does break confidentiality, there may be no real consequences. It can be very hard to sue someone for breaking confidentiality (involving a lengthy and expensive legal process) and even if successful it could prove to be a pyrrhic victory unless some kind of specific loss or detriment can be proven to have resulted because of the breach).

Some confidentiality agreements specifically consider the fact that many people do want to talk with someone about what happened in the mediation afterwards. For example, clause 19 of the agreement to mediate published by the Resolution Institute specifically refers to sharing information with “professional advisors” and to a person within a “legitimate field of intimacy”.

“The Parties and the Mediator will not unless required by law to do so, disclose to any person not present at the Mediation, nor use, any confidential information furnished during the Mediation unless such disclosure is to obtain professional advice or is to a person within that Party’s legitimate field of intimacy, and the person to whom the disclosure is made is advised that the confidential information is confidential.” Clause 19, Resolution Institute sample Agreement to Mediate.

Clause 19 also says that the person to whom the disclosure is made should be advised that the confidential information is confidential. However, it is highly unlikely that simply stating that would be enough, in itself, to create a legal obligation on that person to keep the information confidential.

In workplace conflicts there is often considerable pressure on participants from colleagues and managers who were not directly involved in the mediation to tell them what happened in the mediation. This is particularly likely when the participants have been ‘recruiting’ support or complaining to others in the workplace about the conflict, and they then do not understand why things might have changed subsequent to a mediation.

Other challenges in workplace situations include when a written agreement is to be provided to the human resources department and placed on an employee’s file. If that is later to be used for performance management purposes, it is highly likely that others in the workplace will have access to that agreement.

These kinds of situations can be discussed with parties in advance of the mediation. Simon Roughton nicely described how this can be done (in a private communication with me, shared here with his permission):

“As a general rule I am significantly more relaxed about confidentiality (as in who gets to know what) and take a very pragmatic approach. For example, making it realistic to people that it is human nature there will be a need to share, and I also identify the risk of others who are not in the room putting their lens onto what they are being told. The focus is not so much who gets told what, it’s more on what is the purpose behind them knowing and what does the person have to be aware of when passing information. (Circle of Trust).” Simon Roughton

Informing parties about confidentiality

Sections 3(2) and 9 of the NMAS Practice Standards require the mediator to inform participants about confidentiality before undertaking the mediation process and in relation to private sessions. However, there is a fine line between properly informing the parties and giving them too much information so that they become confused. Consideration should be given to:

- contractual confidentiality and statutory enforcement;

- confidentiality of private sessions;

- the ‘without prejudice privilege’ (if applicable);

- statutory provisions and exceptions to confidentiality;

- parties’ realistic expectations of any confidentiality matters.

It is not enough to state that a mediation will be entirely confidential. The extent of confidentiality must be explained to the parties. This can be done,

- in the agreement to mediate, in terms a confidentiality clause;

- through discussions at intake; and

- during the opening statement before the mediation begins

- at the beginning of any private sessions the mediator has with the parties.

Client self-determination and choice can also be highlighted and discussed when considering parties’ realistic expectations of any confidentiality related matters. It’s far better to have these discussions up front at the start, than having to manage any fallout subsequent to the mediation. Simon Roughton put it very well, suggesting that mediators have an opportunity to:

“make discussions about confidentiality an empowering moment – rather than a ‘you-shall-not-talk’ commandment”. Simon Roughton

Finally, Rachael Field and Neal Wood have made the point that it is also important for mediators to consider how they talk about confidentiality in promotional material. They explain that while many mediators promote their process:

“on the basis of confidentiality as a low risk venture with potentially high quality dispute resolution outcomes, the reality is that the efficacy of confidentiality as a foundational tenet of marketing practice can be brought very much into question, and is far from self evident”.

They suggest that confidentiality is often talked about in blanket terms, without information about the exceptions and inherent risks involved in actually enforcing confidentiality with any certainty. Promoting mediation as simply “a confidential process” may create unrealistic expectations. Field and Wood argue that:

“mediation professionals need to be critical and reflective, not only in terms of how mediation is practised, but also in terms of how substantive theoretical issues sit within the practical reality of the mediation room.”

- How do you speak about confidentiality with your clients / prospective clients (on your marketing materials / website, in sample agreements to mediate, in conversations, etc.)?

- Is there room for more clarity in any of these?

- What kinds of situations can you see confidentiality potentially being problematic for your clients?

- How have you handled these situations in the past? What ideas do you have for handling these situations in the future?

- How can you make discussions with clients about confidentiality an opportunity for empowerment?

Additional reading

Bobette Wolski (2020) Confidentiality and privilege in mediation: concepts in need of better regulation and explanation. UNSW Law Journal 43(4) 1552-1594.

Rachael Field and Neal Wood (2005) Marketing mediation ethically: The case of confidentiality. QUT Law Review 5(2) 143-159.

This is a great overview of all aspects of confidentiality! In particular “What happens if someone breaches confidentiality?” This is a question that I have often pondered and it is difficult when there are generally no real consequences to breaching confidentiality. I suppose by signing a confidentiality agreement we are hoping people act in good faith. I did not think of having lawyers, support persons sign the confidentiality agreement so this was also very valuable insight into pre-mediation requirements.

Discussing confidentiality with lots of transparency with the parties might also be a good method to build trust and allow vulnerability into the mediation process.

Some aspects of confidentiality discussed here have been new to me and raised my awareness and interest to explore this subject in more depth.