There is very little written directly about marketing ethics in the field of conflict resolution. A notable exception is a paper written by Rachael Field and Neal Wood in 2005 about marketing mediation ethically. They caution that “at its present stage of development in Australia, there continues to be a significant level of rhetoric associated with the promotion of mediation, and … this rhetoric requires exploration and reflection in terms of whether it can be said to compromise the ethical nature of the marketing of mediation, and consequently the process and the profession also. They also argued that “the profession must avoid ‘unsupported claims that create unrealistic expectations’ about mediation.

The key here is transparency. How transparent are we about the services we offer, and the benefits and risks involved? Some of the main concerns about unsupported claims are about a gap between the theory of mediation and the practical reality in and outside of the mediation room. Rachael and Neal use confidentiality as an example; however, the point here is that sometimes marketing based on theory of how mediation should work could be misleading, as the reality may not live up to expectations. The authors caution that in any marketing material, explanations need to be very clear about what mediation does and does not offer parties, so they can make an informed decision about its suitability before purchasing.

Similar concerns were raised by Emily Skinner in her PhD research. She noted that most of the millennials in her study thought of conflict resolution as an outcome in which one party ‘wins’, that completely resolves a problem, and that ends in happiness. They didn’t necessarily understand it as a process, let alone one that can be quite challenging; nor did they seem to understand that often an outcome is not ‘perfect’.

As part of preparing our Beyond the Table course module on documentation, I have been reviewing a broad range of documents used by conflict resolution practitioners around the world to consider the different ways they describe services like mediation. There are many similarities, and some interesting differences in the examples I’ve considered.

While I’m sure practitioners believe they are being clear and transparent (and ethical) in what they are describing, disappointingly, I have not found much evidence of improvement in the clarity of descriptions of mediation.

Describing mediation

One thing I’ve noticed is that many practitioners describe their process based on broad and generalised theoretical descriptions of mediation. These descriptions are often not easily understood by laypeople, and sometimes can be misleading. Very few mediators explain in their documentation what will happen in the room (e.g. what steps are involved in their process, what kinds of interventions they use and why). They may well explain in more detail in their initial conversations with prospective clients or during intake / pre-mediation sessions, but this information is not publicly available for review.

Here are some typical examples taken from mediation information documents (often provided to people through a website link or email after an enquiry has been received).

“Mediation is a voluntary, no-cost to low-cost, non-adversarial process through which a neutral third party is introduced into discussion and negotiations between conflicting parties.”

“Mediation is an informal process where a neutral mediator facilitates a process which enables the parties to openly discuss their issues and concerns confidentially.”

“Mediation is a voluntary and informal process where an impartial person (the mediator) helps parties to isolate issues, develop options, consider alternatives and work together to find their own solution rather than having a decision imposed on them by the Tribunal.”

“Mediation helps people settle disputes without the need to go to court.”

“Parties must keep what happens in the mediation confidential, unless required by law or to get professional advice, for example from a lawyer.”

“Mediation is a confidential process. That means that the mediator can only speak about your mediation to other people with your permission. It also means that the mediation parties also can only talk about what they learn in mediation with their advisors or close support people.”

As trained mediators, we can read these statements and know what they mean. However, for the average layperson with no knowledge or experience with mediation, these descriptions are not likely to give them a sense of confidence that they know exactly what they are purchasing. For example, how many laypeople understand the term “non-adversarial”? How many laypeople think of mediation as an “informal process”? It’s certainly informal compared with litigation, but for many prospective clients, the alternative to mediation is not going to court, it’s doing nothing or trying to manage the situation on their own. With these alternatives in mind, mediation seems like the more formal choice!

Some documents also imply that the only (or at least the best) outcome for mediation is settlement. While this may be more appropriate for mediation that is conducted in the shadow of existing or future litigation, even in this situation settlement is not always the right choice. We need to be cautious that we don’t incidentally promote settlement as the only or even the preferred outcome for mediation. For a critical reflection about promoting settlement in mediation read this earlier blog post.

Also, keep in mind that for many conflicts (for example personality differences in a workplace, or interpersonal relationship issues) the idea of “settlement” may not sit well with the people involved. Rather than reaching an “agreement” they may be more interested in having an opportunity to discuss their differences and consider whether they can rebuild a working relationship.

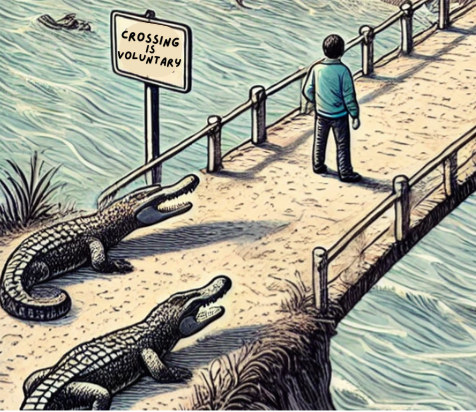

We should also critically consider the concept of voluntariness when it comes to mediation. While technically participation might be voluntary, in that the mediator will not force a party to participate, realistically there may be very limited choice available for a person who is required to attend mediation before going to court or as a condition of their employment. Again, the point here is not whether the process is technically voluntary, but whether using this language has the potential to mislead or create a disconnect with a prospective client.

In their article, Rachael and Neal focus on how mediators describe confidentiality as problematic, and I see many examples of mediators making broad statements about confidentiality that are sometimes over-generalised or misleading. For a critical analysis on the complexities of confidentiality in mediation, see this earlier blog post.

Other language that typically shows up in promotional materials for mediation includes that it is a “quick” and “easy” way to resolve disputes. However, language like this can minimise how difficult mediation can be for participants. Here’s a notable exception to this trend that I found in an information sheet for Mediation for standard claims under the Weathertight Homes Resolution Services Act 2006, NZ Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, that expressly stated “The mediation meeting can be a long and stressful day.”

Describing the mediator’s role

Similarly, looking at how the mediator is described, we see terms like “a neutral third-party”, “independent”, and “impartial”. Most laypeople may not understand what that actually means in practice.

Have a look at the following phrases and ask yourself what a layperson might understand by them:

“A neutral third party is introduced into discussion and negotiations between conflicting parties.”

“The mediator will help the parties work out what the issues are, the positions of each party and possible options for resolution.”

“The mediator is not a judge, but is there to direct the mediation process and stimulate communication between the involved parties.”

“Mediators find solutions that both of you can agree on. A mediator will ask questions to understand your situation.”

The latter statement seems to imply that the mediator is the one finding solutions, not the parties, so it would be reasonable for a prospective client to assume that the mediator is going to suggest outcomes to the parties. The only specific information provided about what a mediator might do is in the last example where it states that the mediator “will ask questions”.

Conclusion

As Rachael and Neal point out in their article, in our field we cannot use typical approaches to marketing, and we need to be very careful to use an honest and accurate approach, especially to continue the developing confidence, credibility and legitimacy of mediation as a dispute resolution profession. I believe we can do more!

- How do you describe your services? Would a complete layperson understand exactly what will happen at each stage of your service provision?

- How do you describe your role? Would a complete layperson understand what you will and won’t do, and what your purpose is?

- Review your documentation for terms such as “voluntary”, “confidential”, “impartial”, “neutral”, “third party”, “settlement”, “agreement”, “non-adversarial”, “informal” and consider whether they are suitable for your context/prospective clients, and how much knowledge they assume in the reader. Can you express things more clearly?

- Do you have a good example of a very clear description of mediation and the mediator’s role to share with me? If so, I’d love to see it!

Rachael Field and Neal Wood (2005) Marketing mediation ethically: The case of confidentiality. QUT Law and Justice Journal 5(2): 143.

Emily Skinner (2019) A Brand New Narrative: Social Attitudes Toward Conflict Resolution and Inefficiency in Marketing and Branding, PhD thesis, Nova Southeastern University. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_dcar_etd/153/

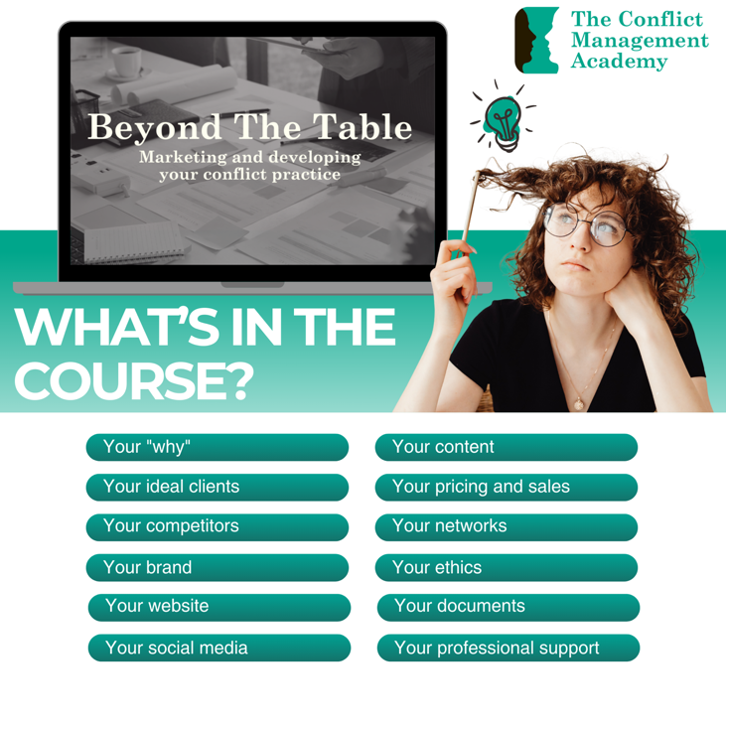

Are you a passionate conflict management professional eager to develop a thriving practice?

Our course is specifically crafted to address the unique challenges and opportunities within the conflict resolution field. Benefit from the insights of industry experts who have successfully established and scaled their conflict management businesses. Engage in practical exercises, case studies, and collaborative discussions to apply your newfound knowledge in real-world scenarios.

As you proceed through the course, you will be supported by coaches and mentors who can help you to apply your learning to your own specific situation and aspirations. By the end of the course you will have a complete business plan and a clear map for your future development.

Find out more about our Beyond the Table course here: https://conflictmanagementacademy.com/beyond-the-table-course