In the past couple of weeks, I have come across a few different mediators in Australia and other countries who have offered, or are currently offering, some version of a contingency fee for their mediation services. This got my attention, and I decided to explore the phenomenon in more detail. I’ve done some research, and also had some fascinating conversations with people with varying views on the topic. I’d particularly like to thank Sarah Blake and Danielle Hutchinson for their insights.

Here’s what I discovered:

Contingent fee mediation

A “contingent fee mediation” (CFM) includes any fee arrangement whereby a mediator’s compensation depends upon some characteristic of the mediated outcome, such as its amount, form, or timing. (Scott Peppet).

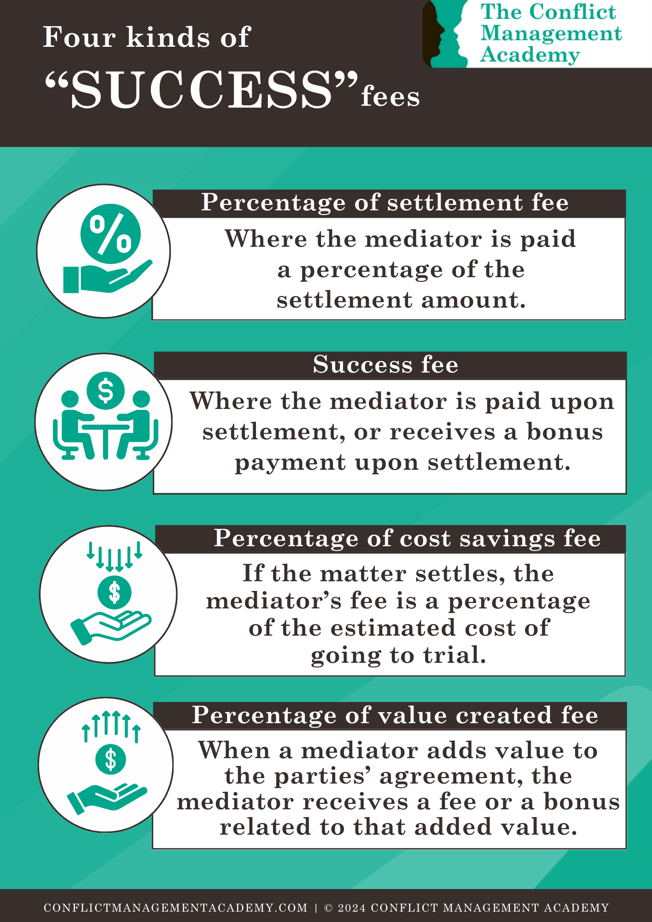

There are four different types of CFMs:

1. Percentage of settlement fee: Where the mediator is paid a percentage of the settlement amount.

2. Success fee: Where the mediator is paid upon settlement, or receives a bonus payment upon settlement.

3. Percentage of cost savings fee. For example, where it is estimated that the cost of going to trial would be $60,000 and the mediator’s fee is agreed to be 10% of that if the matter settles at mediation.

4. Percentage of value created fee. This covers the situation in which a mediator may add value to the parties’ agreement, and when this happens the mediator receives a fee or a bonus related to that added value.

Examples of existing regulation

Most mediation ethics codes, court rules, and commentators have categorically rejected such success fees as part of a broader prohibition on all forms of contingent fee mediation, although there is some movement towards loosening up that approach in a few jurisdictions.

Generally speaking, most US States prohibit mediators charging fees related to the outcome of the process. This is an indicative example from Rule 10.380(f) of the Florida Rules for Certified and Court-Appointed Mediators (2021):

“Contingency Fees Prohibited. A mediator shall not charge a contingent fee or base a fee on the outcome of the process.”

The Model Standards of Conduct for Mediators (prepared in 1994, and revised in 2005 by the American Arbitration Association (AAA), the American Bar Association’s Section of Dispute Resolution (ABA DR) and the Association for Conflict Resolution (ACR)), state:

STANDARD VIII. FEES AND OTHER CHARGES

2.B. A mediator shall not charge fees in a manner that impairs a mediator’s impartiality.

1. A mediator should not enter into a fee agreement which is contingent upon the result of the mediation or amount of the settlement.

2. While a mediator may accept unequal fee payments from the parties, a mediator should not allow such a fee arrangement to adversely impact the mediator’s ability to conduct a mediation in an impartial manner.

Section 9.2 of the ADR Institute of Canada’s Mediator Code of Conduct forbids mediators from having their compensation based on whether or not there is settlement:

A “mediator’s fees shall not be based on the outcome of Mediation, or on whether there was a settlement or (if there was a settlement) on the terms of settlement.”

The Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre has a General Ethical Code for mediators that provides in Section 5:

The mediator has a duty to define and describe any fees for the mediation and to agree with participants as how fees are to be shared and the manner of payment before proceeding to facilitate substantive negotiations. It is inappropriate for a mediator to charge contingent fees or to base fees upon the outcome of a mediation.

The Singapore International Mediation Institute Code of Professional Conduct for SIMI Mediators, Version 2, 10 November 2023, provides:

11.1 Fees : Prior to accepting an appointment, a SIMI Mediator (whether personally or through his mediation service provider) will agree with the parties how his fees and expenses will be calculated, and how, and under what conditions he will be paid by the parties (and if shared between the parties, in what proportions). Subject to any agreement otherwise, a SIMI Mediator who withdraws from a case will return to the parties any fees already paid proportionate to the period following withdrawal.

11.2 Despite Clause 11.1, SIMI Mediators must not suggest to parties that their fees should be based on or related to the outcome of the mediation.

The International Mediation Institute Code of Conduct provides:

4.5.1 Mediators will, before accepting appointment, agree with the parties how their fees and expenses will be calculated, and how they will be paid by the parties (and if shared between the parties, in what proportions). Mediators who withdraw from a case will return to the parties any fees already paid relating to the period following withdrawal.

4.5.2 Mediators will not suggest to the parties that their remuneration should be based on, or related to, the outcome of the mediation.

The Law Council of Australia, Ethical Guidelines for Mediators, updated April 2018, states:

9. Fees A mediator must fully disclose the mediator’s engagement terms and fees to the parties.

Comment

(a) As early as practicable, and before a mediation session begins, a mediator should obtain the agreement of the parties regarding all engagement terms, fees and other expenses to be charged for the mediation, and by whom and when the fees and expenses are to be paid.

(b) The better practice is to record in writing the arrangements in respect of fees and costs.

(c) A mediator should not agree to a fee which is contingent upon the result of a mediation or amount of settlement.

The Australian National Mediation Accreditation System, in the Mediator Practice Standards, provides:

11 Charging for services

11.2 A mediator must not charge fees based on the outcome of a mediation or calculated in a way that could influence the manner in which the mediator conducts the mediation.

The proposed new AMDRAS system includes in the Professional Ethics and Responsibilities, under the heading “Representing their services and competence honestly and transparently”:

2. A RP must obtain agreement from participants about the fees and charges payable and about how those fees and charges are to be apportioned between them. In particular: (i) An RP must not charge fees based on the outcome of a process or calculated in a way that could influence the way the RP conducts the mediation.

Some examples of looser regulation

Despite the fact that most jurisdictions prohibit CFMs, there are some examples of looser regulation around this, in both the US and Europe.

The Commission on Ethics and Standards in ADR (sponsored by Georgetown University Law Center and CPR Institute for Dispute Resolution) drafted a Model Rule (2002) for adoption into the Model Rules of Professional Conduct for consideration by the appropriate bodies of the American Bar Association and any state agency or legislature charged with drafting lawyer ethics rules:

Rule 4.5.5: Fees (c) A lawyer-neutral who charges a fee tied to the timing or fact of settlement or other specific resolution of the matter shall explain to the parties that such an arrangement gives the neutral a direct financial interest in settlement that may conflict with the parties’ possible interest in terminating the proceedings without reaching settlement. The neutral shall consider whether such a fee arrangement creates an appearance or actuality of partiality, inconsistent with the requirements of this Model Rule 4.5.3.

COMMENT [2] While controversial, contingent fee or bonus compensation schemes are sometimes used to provide incentives to participate in ADR or to reward the achievement of an effective settlement. Section (c) does not prohibit such fee arrangements (which some jurisdictions or provider organizations do) but requires the neutral to explain what the effects of such a fee arrangement may be, including conflicts of interest. This Model Rule imposes two obligations on the neutral. The lawyer-neutral is required to assess the possible conflicts attendant to use of such fee arrangements and whether the appearance or actuality of partiality prohibits its use under this Model Rule 4.5.3 (Impartiality). If use of the compensation arrangements is not prohibited under that standard, the neutral is required to disclose the possible consequences of this fee arrangement to the parties.

European Code of Conduct on Mediation

1.3. Fees

Where not already provided, mediators must always supply the parties with complete information as to the mode of remuneration which they intend to apply. They must not agree to act in a mediation before the principles of their remuneration have been accepted by all parties concerned.

2.1. Independence

If there are any circumstances that may, or may be seen to, affect a mediator’s independence or give rise to a conflict of interests, the mediator must disclose those circumstances to the parties before acting or continuing to act.

Such circumstances include:

– …

– any financial or other interest, direct or indirect, in the outcome of the mediation;

– …

In such cases the mediator may only agree to act or continue to act if he is certain of being able to carry out the mediation in full independence in order to ensure complete impartiality and the parties explicitly consent.

The duty to disclose is a continuing obligation throughout the process of mediation.

What’s happening in practice?

Some practitioners, in Australia, the US and the UK report having used some variation of a contingency fee for mediation. See for example the discussion about high-profile lawyer/mediators in the US in Scott Peppet’s article and the quote from Ken Cloke below from his book The Crossroads of Conflict:

“At first, Bill was reluctant to come to mediation and refused to pay for it. Sara said she was unable to pay. In order to get them started, I agreed to begin the mediation, and indicated that if they felt I had not been helpful at the end of two hours they would not be required to pay. I have done this on several occasions when a couple’s conflicts prevent them from agreeing on who will pay for the mediation and have always been paid at the end of the session.” (pages 106-107).

Roger Fisher also went so far as to draft the terms of a contingency fee arrangement in his article Why Not Contingent Fee Mediation (1986).

In 2000, the UK-based InterMediation reportedly justified their no settlement, no fee mediation as being safeguarded by the fact that the mediators are paid by InterMediation, regardless of the outcome of these cases, ensuring that they have no direct financial investment in achieving settlement.

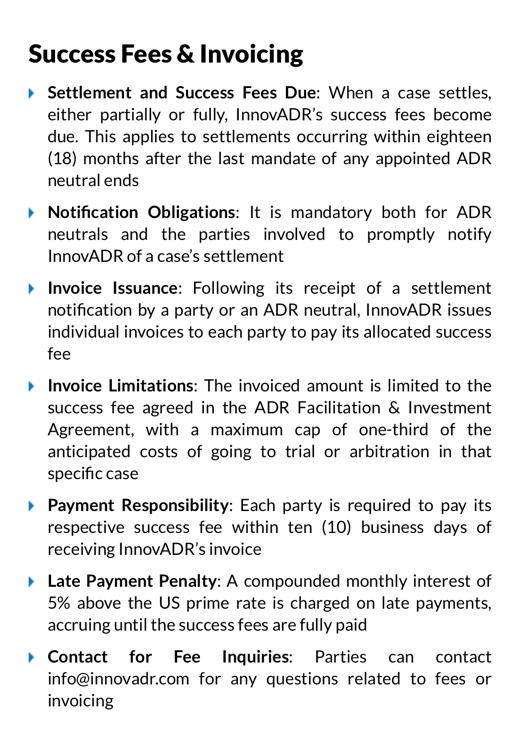

Recently, the newly launched Swiss-based InnovADR also advertises no settlement, no fee policy. Similarly to InterMediation, clients who engage in mediation through InnovADR do not pay if the matter does not settle, but InnovADR pays their mediators for their time irrespective of the outcome of the mediation. This is how their website explains their fee structure:

Scott Peppet from the University of Colorado Law School has argued in support of a limited kind of CFM. He proposed the following rule as a guide for future mediation ethics codes:

A mediator shall not take a fee contingent on any aspect of a mediation unless:

(a) the mediator discloses, in writing, the fee arrangement and its potential consequences, the mediator recommends that the parties consult with counsel about the fee arrangement, and, prior to the mediation, all parties provide informed consent in writing and after an opportunity to consult with counsel;

(b) in court-ordered mediation, the fee arrangement is disclosed to and approved by the court prior to the mediation; and

(c) the fee arrangement does not create an appearance or actuality of partiality toward one party.

Arguments for and against

Here is an overview of some of the arguments for and against CFM:

Discussion

Increased access to justice, or access to second class justice?

Those in favour of CFMs argue that they lower the barrier to entry for mediation, as parties do not have to pay upfront fees, which makes mediation more accessible, especially for those who might not afford the costs otherwise. While this may be true in some cases, there are a range of free mediation services available for people through government-funded and not-for-profit organisations, and also a range of pricing structures in the Australian mediation market. Given the number of people who have completed mediation training over the last few years, many of whom are struggling to make a living as a mediator and looking for work, there doesn’t seem to be a shortage of mediators available, offering mediation at a range of price points, to support clients who need their services.

Parties engaging in mediation with a CFM also bear less financial risk. They do not have to pay for the mediator’s services if a settlement isn’t reached, which can encourage them to pursue mediation as a dispute resolution option without fear of extra costs that may be thrown away if the process fails and they are required to litigate. Sarah Blake notes that the blended process of mediation/arbitration (“med-arb”) can address some of those risks, as an outcome is part of the process, whether or not the parties settle through mediation.

Counter-intuitively, CFMs may limit access to mediation for parties involved in more complex and challenging disputes. This is because mediators might be disinclined to take on complex cases that require extensive time and effort and in which the likelihood of reaching a settlement is low. This could make it harder for some clients to find a mediator, or leave them with fewer choices of mediators, willing to take on their mediation.

These more complex cases may end up being mediated by less experienced mediators, who might be more willing to offer CFMs to get work. This could be problematic for both the mediator, who might end up out of their depth, and the parties, who might not get the highest level of skills and experience needed to work with their complex conflict. This also highlights some of the challenges for new mediators in a sole-practice environment, who rarely have access to the mentoring / apprenticeship type support for newer mediators to gain experience under supervision.

The widespread use of CFMs by mediators could also decrease access to justice because mediators might increase their fees to cover the risk of mediations in which they are not paid. The pressure to provide CFMs might also lead to some mediators leaving practice altogether.

Both Sarah Blake and Danielle Hutchinson commented that a related problem is the mediator’s self-interest in agreeing to conduct a mediation in the first place, and the level of transparency by the mediator when accepting or declining a case. For example, Danielle Hutchinson suggests that in situations in which a mediator has been requested to take on a challenging case on a CFM bases, the mediator might say: “I can’t take this mediation on the basis of no-settlement no fee as this matter is very complex and it may not be possible, or even appropriate, to attempt to reach agreement on every issue within a single session. However, I do think there is enormous benefit in …. “.

There is also the related question of whether mediators are discerning enough about the suitability of the dispute for mediation, the extent to which their process is suited to the parties’ needs, or whether they have they necessary skills and/or experience. This speaks to the need for more flexibility around process and bespoke process design. Danielle Hutchinson commented that in the Global Pound Conference Series reports it was suggested that the most dispute-savvy parties wanted mediators to collaborate with them more to design processes to fit their needs, rather than take them through a standard process.

Risk of exploitation by the parties, or incentive to better screen cases?

There’s a concern that parties could abuse a CFM system by engaging in mediation with no genuine intention to settle, simply to exploit the free mediation to engage in a ‘fishing expedition’ or ‘tick a box’ that mediation has been attempted so that they can then proceed to court. This could result in wasted time and resources for both the mediator and the other party. Even without the risk of exploitation, this could occur because the matter was genuinely not able to be settled despite everyone’s best efforts.

However, as Danielle Hutchinson commented, this might actually be a benefit in disguise, in that it would encourage mediators to engage in better screening of parties and the dispute before agreeing to mediation, and the mediator investing more time and effort into properly preparing the parties pre-mediation.

Alignment of Interests or conflict of interests?

By tying the mediator’s compensation to the successful resolution of the dispute, some have argued that the mediator’s interests are aligned with those of the parties involved (all want settlement to occur for their individual benefits) and that this may incentivize the mediator to work more diligently towards finding a resolution. Mediators might employ more creative and persistent efforts to ensure that the parties reach an agreement. This argument does assume that mediators need an added incentive to do their best, which I imagine many mediators would find objectionable.

Critics of CFMS argue, however, that they create a conflict of interest for mediators, in that mediators may be tempted to push for settlements, even if they are not in the best interest of the parties, solely to ensure their own compensation. Mediators facing a possible reluctance to settle by one or both parties might react by increasing pressure on a weaker party to agree or avoiding asking the hard questions or ‘hot spots’ because it might risk potential resolution.

Mediators might also prioritize reaching a settlement quickly, rather than engaging in a thorough exploration of the issues and interests involved in the dispute, accepting a “quick fix” rather than a sustainable, long-term solution. Sarah Blake suggested that in her experience, “most mediators will push for an agreement – so the problem is more that the agreement might tend to focus on financial or legal risks rather than a more interest-based and complex agreement which will be more sustainable”. This also links back to Danielle Hutchinson’s suggestion above about how mediators could approach complex cases that they did not wish to accept on a CFM basis.

This may also raise questions about potential misalignment between the clients’ needs and the particular mediator’s approach. For example, some mediators will focus more on a distributive approach to negotiating settlement, whereas others will take a more interest-based and relational approach. Added to this is the fact that many prospective clients do not really understand the variety of approaches and process models available in the field of mediation. Frequently, parties do not know what they can and cannot ask for.

The argument in favour of CFMs based on an alignment of interests also assumes that settlement is the best outcome for everyone involved, which is not always the case. While it is more likely to be the main concern for parties who are trying to settle a matter that is pending litigation, even then there are circumstances in which settling, or settling on the terms offered, is not the best choice. The question is whether mediators are prepared or willing to respond with alternatives, as suggested by Danielle Hutchison above.

For mediators who work as employees or as casual panel members, it is arguable that there is an implied pressure to settle cases that they mediate in order to keep their employer or organisation happy. While the mediator in those cases gets paid irrespective of the outcome, there is always the potential for the mediator to be performance managed or to be allocated fewer mediation based on their “success rates”.

Whether or not mediators are actually influenced by CFMs, there is always the risk that others will perceive that mediators may be influenced by their own self-interest in getting paid.

Settlement focus or broader benefits?

While some commentators argue that CFMs are beneficial for promoting a settlement culture in mediation, others argue that this is in fact detrimental as it narrows the focus of the process to reaching an agreement, rather than considering broader potential benefits and outcomes.

CFMs fail to recognize the true value of a mediator’s services. Despite a mediator’s best efforts, a case may not settle at mediation for reasons unrelated to the mediator’s skill and efforts. Furthermore, there is still value in a mediation not resulting in settlement even in a pre-litigation context, such as a narrowing of issues, a preview of witnesses, a better understanding of the other side, and, where appropriate, an early neutral evaluation.

Self-determination of the parties and the mediator to agree on whatever fee arrangement they want

There is tension between parties’ expectations and what is possible within the confines of ethics and standards. Scott Peppet argued in his article that parties’ self-determination should include them being able to tailor the mediator’s most basic obligations and functions to suit their needs (even if outside of the mediator’s code of ethics). In other words, if parties and the mediator are happy to negotiate an CFM, they should be permitted to do so. There is an important conversation required within the profession about what self-determination means, and its limits.

CONCLUSION

Mediators need both integrity and experience to ensure that their power in mediation is managed responsibly. The isolated nature of our work makes it hard to identify when mediators are breaching ethical boundaries, and it seems that the use of CFMs may create new opportunities for such boundaries to be blurred.

As a profession, in Australia and many other countries, we have long resisted the notion that success must mean a settlement agreement. We have also put in place ethical rules and regulations to ensure that the power of the mediator is constrained to minimise risks relating to conflicts of interest and impartiality. Proponents of CFMs argue that they can be used ethically when there is sufficient transparency and informed choice; however, this would require changes to many codes of ethics currently in existence.

Whether or not you support CFMs, the discussion has given rise to some interesting questions about self-determination, transparency and flexibility around process, the distinction between process responsibility and outcome responsibility, the quality of our pre-mediation screening and preparation of parties, and the place of mediation in the available conflict resolution processes.

1. Have you ever used CFMs?

2. Are you in favour or against CFMs?

3. Which arguments (for or against) resonate most with you?

4. Are there specific situations in which you think CFMs are acceptable?

5. Why is there a shift towards CFMs despite the majority of jurisdictions prohibiting them?

6. Is the problem that people don’t want to (or can’t afford to) pay mediators, or is it something else?

7. Should we be focusing on better screening and assessment, as well as working with parties to tailor a process that best suits their needs?

I’d really love to hear your thoughts on this controversial topic!

Marc Bhalla (2024) Show me the money: explaining why contingency fees don’t work in mediation and how mediators can get paid in full. Slaw Magazine.

CPR-Georgetown Commission on Ethics and Standards in ADR. (2002) Model rule for the lawyer as third-party neutral.https://drs.cpradr.org/rules/protocols-guidelines/ethics-codes/model-rule-for-the-lawyer-as-third-party-neutral

Roger Fisher (1986) Why not contingent fee mediation? Negotiation Journal 2(1):11-13. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1571-9979.1986.tb00334.x

Patrick Van Leynseele (2019) Some thoughts about success fees for mediators. Bjutijdschiften Blog. https://www.bjutijdschriften.nl/tijdschrift/tijdschriftmediation/2019/4/TMD_1386-3878_2019_023_004_003/fullscreen

Litchfield E. and Hutchinson D., The North America Reports Global Pound Conference Series 2016-17 https://www.imimediation.org/2020/02/11/north-america-report-release/

Steve Mehta (2009) Contingecy fee: The dark lord of mediation fees or the fee that shall not be named. Mediate Matters Blog and Mediate.com Blog.

Scott R Peppet (2003) Contractarian economics and mediation ethics: the case of customzing neutrality through contingent fee mediation. Texas Law Review 87: 227, available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/535

Phyllis Pollack (2024) Mediation is not always about settling! Mediate.com blog, 15 February 2024. https://mediate.com/mediation-is-not-always-about-settling/

Mitchell Rose (undated) When results shouldn’t matter: the case against mediator contingency fees. ADR Institute of Canada, ADR Perspectives.

https://adric.ca/when-results-shouldnt-matter-the-case-against-mediator-contingency-fees/

Mitchell Rose (undated) 5 Reasons why mediators should not charge contingency fees. Mitchell Rose Blog https://mitchellrose.ca/why-mediators-should-not-charge-contingency-fees/

Omar Shapria, (2016) A theory of mediators’ ethics, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. Page 197.

Donald L. Swanson (2018). Contingent fees or success fees for mediators: why not? Mediatbankry Blog. https://mediatbankry.com/2018/07/10/contingent-fees-or-success-fees-for-mediators-why-not/