* Thanks to Rebekka Kornmehl, Danielle Hutchinson, and Carol Bowen for their helpful feedback on this content.

People in the conflict resolution field typically think of mediation as a client-centered, informal, and flexible approach to managing conflict. However, as highlighted by participants in the Symposium for Access to Justice for Autistic People in ADR in Melbourne last November, despite growing awareness over recent years, the current frameworks may still not be meeting the needs of neurodivergent individuals as effectively as they could. Recent research conducted by Oz Susler at La Trobe University into autistic people’s experiences of mediation found that they experienced the process as incredibly stressful and that they struggled to participate.

Defining neurodiversity, neurodivergence and neurotypical

There is a great deal of confusion about the terms neurodiversity, neurodivergence and neurotypical.

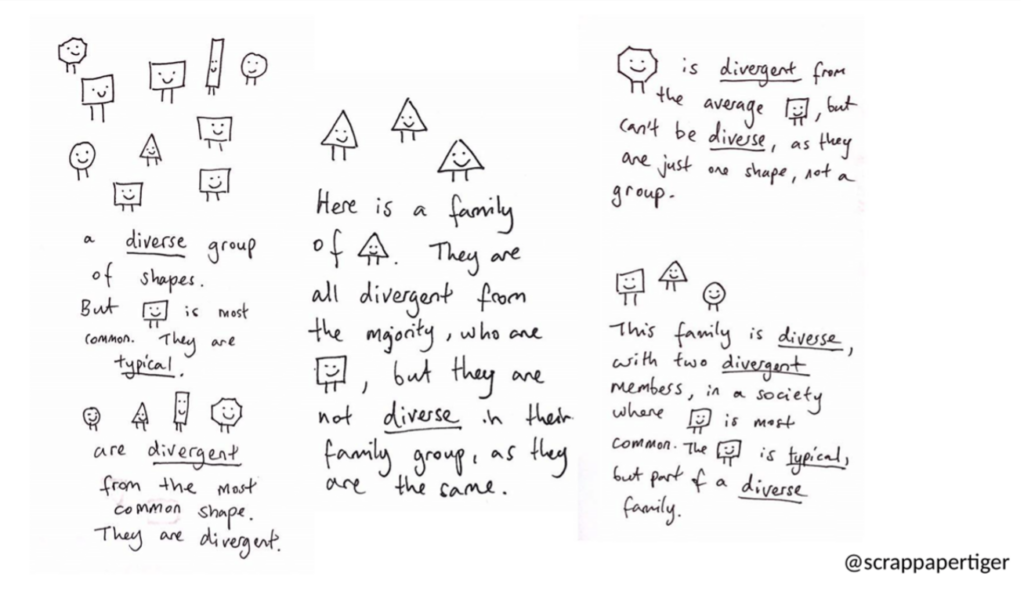

To help understand the concepts we are going to discuss, it’s first useful to consider the notions of “diverse”, “typical” and “divergent” more generally. This image below from @scrappapertiger is a very clever way to show the difference between these concepts using shapes.

Understanding these broad concepts is useful when we then apply those categories to neurotypes. A neurotype is a category (like the shape example above) used to group people who are similar to one another in the way their minds and nervous systems work. Note that similar doesn’t mean exactly the same – we might categories a lot of shapes as “circles” but there is considerable variation even with the category of “circle”.

Just like the square shape in the example above was the most common, most people can be categorised into a group described as “neurotypical”. A person who is described as neurotypical has a mind, nervous system and body that is similar to the majority of people in the society in which they live. This means that they think, perceive, know, develop, process information and interact with the world in ways that most people perceive to be typical. Note that typical is not the same thing as normal. Nick Walker, author of Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities clarifies that there is no such thing as a ‘normal’ mind:

“When we say someone is neurotypical, we don’t mean they were born with a specific type of brain, and that the type of brain they were born with is the “normal” type—because that’s just nonsense… When we say someone is neurotypical, what we mean is that they live, act, and experience the world in a way that consistently falls … within the boundaries of what the prevailing culture imagines a person with a “normal mind” to be like.” Nick Walker.

However the world is not just made up of squares (ooops, I mean neurotypical people). There are many other neurotypes in the world. The beautiful diverse mix of neurotypes in the world is known as “neurodiversity”.

“Neurodiversity is the variation among minds. Each human being differs to some extent from every other human being, with respect to their neurocognitive functioning—how they think, perceive, know, and develop, how their minds process information and interact with the world. Neurodiversity is the name for this phenomenon.” Nick Walker.

Neurodiversity is not just about different brains

Nick Walker insightfully observes that neuro- doesn’t mean brain, it means nerve. So neurodiversity is not just about differences in people’s brains, but it is also about differences in our nervous systems and how we move our bodies.

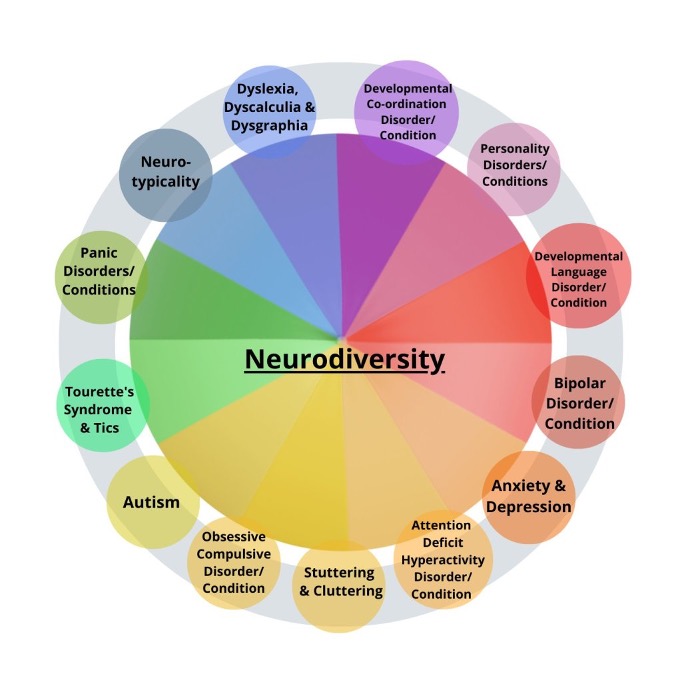

Neurodiversity includes people who are perceived as neurotypical as well as people who are perceived as being neurodivergent for many different reasons. The image below shows a broad range of neurodiversity in any society.

A person who is neurodivergent has a mind and nervous system that prompts them to experience the world and/or behave in ways that the dominant culture judges to be outside what is typical of the majority. When we call someone neurodivergent, we don’t mean that they aren’t “normal,” rather we mean that they aren’t neurotypical, in that they don’t match what the majority of people in a prevailing culture/society believes people should think and behave.

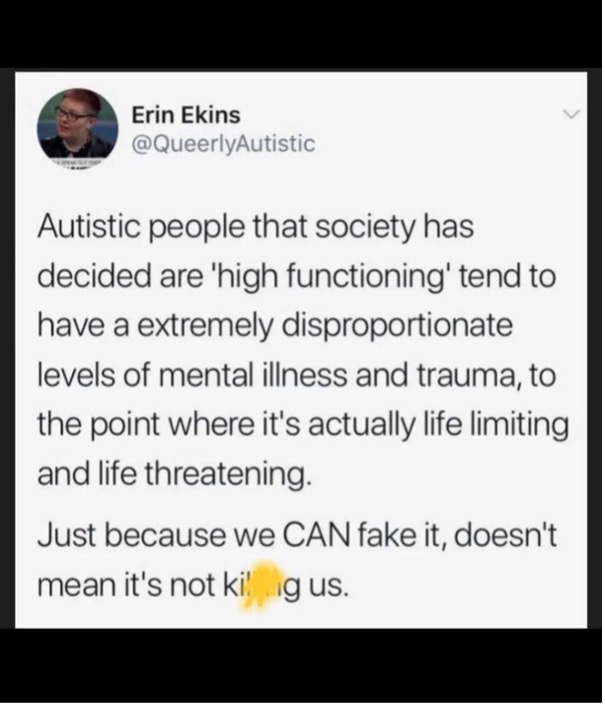

Many neurodivergent people can “pass” as neurotypical, in that while their internal world is different to the majority, they are able to convincingly behave in a way that is consistent with the standards of the majority. This behaviour is known as “masking” and people who can do this are sometimes referred to as ‘high-functioning’. However, continuously behaving in a way that doesn’t come naturally to your neurotype can often require a lot of energy and can lead to burnout.

Defining mediation

When discussing how mediation might be more inclusive of people who are neurodivergent, an initial challenge is clarifying what we mean when we refer to mediation. There is no universal agreement on the key elements of mediation. Mediation is not one thing: it varies greatly according to the model used, the individual practitioner’s style, and the context in which it occurs. Even within a system like the Australian Mediator and Dispute Resolution Accreditation System (formerly the National Mediator Accreditation System), there is enormous diversity in the way individual mediators conduct their mediations.

While mediation can be flexible, it does depend on the ability and willingness of the practitioner to stay alert to their own assumptions, normative biases and possibilities to work outside their comfort zone. For employed mediators, there may be limited opportunities to vary the organisation’s mandated process (e.g. in court-connected mediations conducted by tribunal members according to inflexible guidelines and time constraints).

Most variations of mediation are based on neurotypical approaches

Mediation (at least as it’s discussed in much of the literature and in many commercial training programs) tends to be based on a very narrow neurotypical perspective about how people experience conflict, and how best to communicate about it, so that people can manage or resolve it effectively.

Some common attributes of mediation that can work for predominantly neurotypical participants, but that can be problematic for neurodivergent people include:

Many mediations are conducted face-to-face;

Mediations often take place in an environment that chosen by the mediator, and unfamiliar to the parties;

A joint mediation session is typically conducted in a compressed timeline, with intense sessions often crammed into a few hours, assuming that participants can engage in communication, information processing and emotional regulation fairly quickly;

Mediations tend to be process driven, with specific requirements about who can communicate, how, and about what, at different stages in the process;

Mediation (especially in the facilitative model) involves a series of transitions between stages with different ‘rules’ for what happens during those stages;

Mediation tends to be very talk-focused, and there is an expectation that participants verbally communicate directly with the mediator and the other participants;

Mediation assumes that parties can and will regulate their emotions throughout the process;

Mediation assumes that people are capable of, and should engage in, perspective taking and/or imagining a variety of potential solutions;

Many mediators have only a rudimentary understanding of neurodiversity and are not equipped to understand differences in communication styles and empathy between neurotypical and neurodivergent clients, they may have blind spots that prevent them from helping clients to bridge gaps in understanding

This means for some neurodivergent people, particularly those who have specific needs in connection with processing (sensory or informational) and emotional regulation, there is a distinct possibility that they may be starting a mediation process at a much higher level of emotional dysregulation. Couple this with additional expectations around verbal and non-verbal communication and it starts to become clear that the cumulative burden of these mediation “norms” can make participation difficult and sometimes impossible.

What suggestions have been made to make mediation more inclusive of neurodiversity?

Expanding the intermediary program

During the Symposium, there were presentations about the intermediary program offered in some Australian courts, and suggestions that it could be expanded to support autistic people to participate in court-connected mediation.

“The intermediary program assists criminal justice stakeholders to communicate clearly with victims and witnesses who are giving evidence in police interviews and during court proceedings.” Victorian State Government Intermediary Program website.

The intermediary programs are designed primarily to support the purposes of the justice system; in particular, providing the court with the required information / evidence. Other benefits are secondary to this, including reducing the individual’s trauma experience and providing better justice outcomes for participants. It appears that the program aims to support vulnerable participants in a fairly hostile system instead of redesigning the system so that it is inherently supportive, inclusive and equitable for everyone.

There are no doubt limits to how much the criminal justice system can be changed, however when it comes to improving how mediation works, especially when it occurs outside of the court system, there may be fewer limitations.

Pre-mediation coaching

Pre-mediation coaching has also been suggested as a way to support neurodivergent people to prepare to participate in mediation. Rather than diving directly into mediation, preparatory conversations can help identify individual preferences and comfort zones, allowing for a tailored approach that minimizes stress and maximizes participation.

However, it is important that coaching and accommodations are not based on a deficit model, aimed at supporting someone to adapt to a neurotypical framework. This is where the double empathy problem arises – why should the neurodivergent person be the one who has to manage their processing and communication needs to fit within a neurotypical system? Why not use pre-mediation coaching to support neurotypical people to change their assumptions, expectations and behaviours to fit neurodivergent participants’ needs.

Accommodations

Many conversations around providing access to mediation for neurodivergent people are about offering special accommodations. In other words, where a person is unable to fit the “standard” process, they can request that the process be adapted to allow them to participate more effectively. While many neurodivergent people can benefit from accommodations, they should not have to identify themselves as neurodivergent to ask for or be eligible for these changes. As Dan Berstein said in his presentation at the Symposium, “people shouldn’t have to audition to be able to say what they need”.

Flexibility

Let’s contrast accommodations (removing obstacles for individuals – reactively) with flexibility built into the system (changing the system so that individual modifications are not required – proactively). The framing of providing “accommodations” for people who need special help is itself problematic. It identifies the individual as somehow deficient for not being able to fit the existing system, rather than the system as being deficient for not being suitable for a broad range of people to participate. I’ve seen this framing in the way schools attempt to support neurodivergent students. While well meaning, many of the supports offered are aimed at fitting the child into a typical system, rather than adjusting the system to support a broader range of children.

Dan Berstein draws attention to the idea of universal design—adopting a flexible and adaptive framework that serves all participants without the necessity of disclosing diagnoses or fitting into rigid labels. Why not reimagine mediation to accommodate various needs, so we don’t have to identify and provide special variations for people who don’t fit our existing way of doing things?

Educating mediators

A significant theme in the Symposium discussions was the need to dismantle misconceptions about neurodivergence. Neurodivergent individuals bring diverse perspectives and strengths to any setting, including mediation. Yet, a lack of understanding about how such differences manifest can lead mediators to misinterpret behaviours, often viewing them through a lens of resistance or non-compliance. This can lead to mediators losing their impartiality and even discriminating against neurodivergent individuals.

Neurotypical mediators might unconsciously impose their communication and problem-solving styles on others, limiting their ability to truly engage with and adapt to the needs of neurodivergent participants. Instead, embracing flexibility and being open to designing processes around all participants’ unique needs can lead to more successful outcomes.

This leads to another important consideration in dismantling misconceptions which is ensuring that neurodivergence, mental health and capacity are not conflated. For example, the cumulative impact of inflexible processes may be that neurodivergent participants are disproportionately more likely to experience high levels of anxiety. Where anxiety reaches levels where the nervous system is triggered into flight, flight or freeze the ability to engage in higher order thinking becomes reduced. While this phenomenon can occur in both neurodivergent and neurotypical people alike, the cumulative burden on neurodivergent people may disproportionately impact their meaningful participation. When thinking about it in this way, we can start to see that shifting to a more universal design approach where the focus is on helping to embed flexibility we have the potential to reduce anxiety for the purpose of supporting meaningful participation more broadly. Moreover, it reduces the risk that mediators conflate neurodivergence directly with an inherent reduction and/or lack of capacity to meaningfully participate.

A challenge

I challenge you all to envision what a truly inclusive mediation process would look like in practice. This involves not only reimagining the process itself but also rethinking the very principles that underlie mediation. By adopting a philosophy grounded in inclusivity and flexibility, mediators can elevate their practice to meet the evolving needs of all individuals. The journey toward inclusivity is ongoing and demands both courage and creativity.

Here are some simple steps to get started:

Learn about neurodiversity, including how it relates to mental health and capacity. (There are some good references below to get started).

Take some time to write down clearly and in detail a description of what you do – how your process works, exactly what happens at each step of the service provided, what tasks/interventions/skills you use.

Clearly and in detail describe what you expect participants to be able to do in your mediation work. So often this is simply assumed rather than articulated (to ourselves as well as to our clients).

Consider which of these activities / expectations might be difficult for people who are neurodivergent.

Identify areas of your practice where you currently provide flexibilities. Identify areas of your practice where you could add extra flexibilities.

Explore ways to offer flexibility to every client (not just those who you think might need “special support”).

A great overview of these concepts, with useful infographics can be found on the stimpunks website: https://stimpunks.org/glossary/neurodivergent/

Danielle Hutchinson’s excellent blog about neurodiversity and conflict:

https://resolutionresources.com.au/tag/neurodiversity/ and her webinar on demand: https://conflictmanagementacademy.com/webinar-on-demand-neurodiversity-and-conflict/

Dan Berstein’s excellent book “Mental Health and Conflicts” and his online course Ready for Anything: https://conflictmanagementacademy.com/ready-for-anything/

Download our client brochure listing suggested flexibilities to consider in your practice. Preparing something like this to provide to your clients can assist people to ask for what they need, and also give them some guidance about the kinds of things they could request.