This post has been written by Judith Rafferty, adapted from her Open Educational Resource (OER) Neuroscience, psychology and conflict management (2024), licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial 4.0 Licence by James Cook University.

Neuroscience, psychology and conflict management

In a previous post, I discussed the value of neuroscience and psychology knowledge to inform conflict management theory and practice. In this post, I discuss specific learnings gained from cognitive psychology, focusing on memory and the phenomenon of priming.

Memory in conflict management

Conflict management practitioners – these include mediators, facilitators, coaches and negotiators – and negotiating parties often need to handle complex issues and juggle multiple pieces of information during a conflict management process. For example, conflict parties frequently must remember what they said, thought and did in the past, and process new information for future decision-making. These tasks require all types of the human memory, including:

sensory memory

short-term memory

long-term memory

In this post, I focus on long-term memory and the phenomenon of priming, due to its applicability to conflict management. Before discussing priming in more detail, let’s have a brief look at what the long-term memory comprises.

Long-term memory

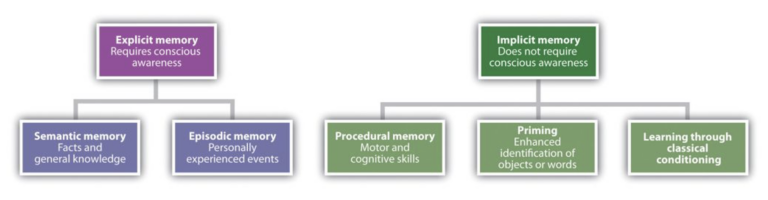

The long-term memory can be categorised as explicit and implicit memory.

The explicit memory, also known as declarative memory, refers to the type of memory that a person is consciously aware of. “You know that you know the information” (Gluck et al., 2020, p. 280). It comprises both memory of facts and general knowledge (semantic memory) and memory of personal experiences (episodic memory).

The implicit memory, by contrast, refers to memory that operates without the learner being consciously aware of it. Implicit memory is formed by:

procedural memory

priming

learning through classical conditioning

It’s also important to remember that each client may need different types of paperwork, so you adapt and tailor your documents to each client and context.

Priming

Priming is a psychological phenomenon where exposure to a stimulus influences how we respond to subsequent stimuli, and how we perceive and interpret new information. As defined by Gluck et al. (2020), priming is

“a phenomenon in which prior exposure to a stimulus can improve the ability to recognize that stimulus later” (p. 88).

Similarly, Kassin et al. (2020) describe priming as

“the tendency for frequently or recently used concepts to come to mind easily and influence the way we interpret new information” (p. 118).

In essence, priming makes certain concepts or ideas feel familiar, even if we aren’t consciously aware of the exposure.

For example, research has shown that if we’re subtly exposed to specific words or images, we may later be more likely to recognise or choose something related to those stimuli (Gluck et al., 2020; Goldstein, 2019; Kassin et al., 2020).

The impact of priming on social behaviour

Exposure to a stimulus can also lead people to behave in a particular way without their awareness, especially when the stimulus was presented subconsciously. The impact of priming on social behaviour has been demonstrated in research, including in a series of provocative (and debated) experiments by Bargh, Chen and Burrows (1996). In this study, participants were primed with different words that were thought to influence their behaviour.

For example, in experiment 1, participants were primed to activate either the constructs “rudeness” or “politeness” and were then placed in a situation where they had to either wait or interrupt the experimenter to seek some information. The research found that participants whose concept of rudeness was primed interrupted their experimenter more quickly and frequently than did participants primed with polite-related stimuli.

In experiment 2, participants were primed with words that activated elderly stereotypes. The study found that participants for whom an elderly stereotype was primed walked more slowly down the hallway when leaving the experiment than did control participants, consistent with the content of that stereotype.

How does priming relate to conflict management?

The phenomenon of priming can both help understand what creates conflict and how we can support parties in conflict management/ resolution. Most of the publications discussed in this post focus on mediation, but many of the findings could also find application in other conflict management process such as group facilitations and one-on-one conflict management coaching.

Priming in mediation

Daniel Weitz, in his article The brains behind mediation: Reflections on neuroscience, conflict resolution and decision-making discusses how priming can influence the mediation process. He suggests that using words like “listen to,” “hearing each other,” “dialogue,” “options,” and “future” in their opening statements, mediators may be able to “prime” parties for collaboration rather than competition (p. 478).

Similarly, Hoffman and Wolman in their article The psychology of mediation note that the mediator’s initial description of the mediation process is the most powerful form of priming in mediation. Based on priming studies (which the authors mention but don’t specifically list), they suggest that mediators may wish to include expressions such as “being ‘flexible’ and ‘open-minded,’ the goal of reaching ‘a fair and reasonable resolution,’ and the need for ‘creativity’ and ‘thinking outside the box’” in their opening statements (p. 3).

Beyond the mediator’s opening statement, Sourdin and Hioe, in their article Mediation and psychological priming, discuss other opportunities for priming during the mediation process. They suggest that mediators can “strategically moderate the environment” to foster a positive atmosphere and encourage successful outcomes (p. 79). Such moderation can be achieved, for example, by carefully selecting and setting up the physical location of the mediation, including considerations of room colour, temperature, and the provision of food and water.

Amanda Carruthers, in her article on The impact of psychological priming in the context of commercial law mediation, explores factors such as the physical appearance of the mediator and legal representatives, the choice of venue, language use, and the influence of stress and references to money. She concludes that mediators and legal practitioners should avoid overt priming cues related to strength, power, and money to improve the positions of both parties in a commercial mediation.

How priming can affect perception

People are particularly likely to rely on the priming effect when new information is ambiguous. This is because we rely more on top-down processing than bottom-up processing when we are confronted with an ambiguous stimulus.

Bottom-up processing begins with our receptors, which take in sensory information and then send signals to our brain. Our brain processes these signals and constructs a perception based on the signals. When our perception depends on more than the stimulation of our receptors – and this is frequently the case when information is ambiguous – we speak about top-down processing. During top-down processing, we interpret incoming information according to our prior experiences and knowledge. This process is frequently referred to as concept or schema-driven. As we learned earlier, when we have been primed, frequently or recently used concepts come to mind more easily and influence the way we interpret new information.

In her blog post Priming in psychology, Kendra Cherry discusses how the priming effect influences what people hear when confronted with ambiguous auditory information, referring to the 2018 Yanny/Laurel viral phenomenon.

As an example for visual perception, Lisa Feldman Barrett explains in her book How Emotions are made how priming can significantly influence our visual perception of others’ emotions. She emphasises that facial expressions are often much more ambiguous than many popular readings suggest, which would make us particularly susceptible to the effects of priming. For instance, if we’re told a person in a photo is screaming in anger, we are more likely to see anger in their expression, even if this is inaccurate.

The person might actually be celebrating something positive, such as winning an important tennis match, potentially involving a whole mix of (positive) emotions, but the priming narrows our interpretation. With contextual information provided, we are likely to interpret the facial configuration more accurately than when taken out of context.

How does the priming effect and perception relate to conflict management?

A mediator might misinterpret facial configurations of parties in a mediation, perceiving emotions like anger, based on preconceived ideas of how people may “show” that emotion on their face, or influenced by comments made by the other mediation party.

Knowing about priming can sensitise us to potential misinterpretations of emotions and encourages us to use multiple cues and information to perceive parties’ emotions more accurately. For a more detailed discussion on the cues that we can use to more accurately perceive others’ emotions, see Chapter 3, Topic 3.4 in Neuroscience, psychology and conflict management. These cues and the topic of emotions in conflict is also discussed in much more detail in Sam Hardy’s course on Working with Emotions in Conflict.

Priming to improve inter-group relationships

Recent research by Capozza, Falvo and Bernardo explored whether activating a sense of attachment security through priming can reduce the tendency to dehumanise “outgroups”—groups with which individuals don’t feel a connection. They conducted two studies:

The first study primed attachment security by showing participants images of relationships with attachment figures and then measured how they humanised an outgroup, in this case, the homeless.

The second study had participants recall a warm, safe interaction to activate a sense of interpersonal security and then measured how they humanised another outgroup, the Roma.

Both studies found that attachment security led to greater humanization of outgroups, with the second study showing that increased empathy played a key role in this effect. These findings suggest that fostering a sense of security can enhance intergroup relations, which has implications for intergroup conflicts. The successful use of priming to boost feelings of security highlights the importance of applying cognitive psychology to conflict management.

The calming effect

Capozza, Falvo and Bernardo, in their article, discuss several further positive effects of security priming, many of which are relevant to conflict and conflict management/resolution. For example, they emphasise the calming effect of security priming, noting that “even a momentary sense of security can shift the attention from one’s needs to others’ needs…” (p.3).

Conflict management processes often aim to help individuals in conflict consider the needs and concerns of others. Understanding the calming effect of security priming and its ability to foster perspective-taking may provide conflict management practitioners with additional strategies to support their clients. Such strategies could consider aspects like:

The choice of physical setting for a mediation or coaching session (or other conflict management process).

The language used by the practitioner, such as during the mediator’s opening statement.

The types of questions the practitioner asks throughout the process.

Remaining questions and considerations

This post explored the priming effect and its relevance to conflict management, particularly in understanding why conflicts arise and how practitioners can support parties to manage or resolve them. Research suggests that there are multiple opportunities to prime parties during a conflict management process, such as mediation, as discussed in the sources mentioned throughout this blog. However, many questions remain, such as how much control a practitioner truly has over priming in a conflict management process Additionally, practitioners should consider the ethical implications, including the potential for manipulation, when applying priming techniques to their practice.

A full reference list of the readings referred to in this post that have not been linked in the text can be found here.

Author Bio

Judith Rafferty is an Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at the Cairns Institute, JCU, and a Senior Trainer at the Conflict Management Academy. She integrates over 12 years of experience as a conflict management practitioner, researcher, and educator/trainer. She holds a PhD in Conflict Resolution, a Master of Conflict and Dispute Resolution, a Graduate Business Administration Diploma, and a Graduate Certificate in Psychology. As a Senior Lecturer and former Director of the postgraduate Conflict Management and Resolution program at James Cook University, Judith played a key role in developing curriculum and training resources that assist professionals in navigating complex conflict situations.

Judith can be contacted on:

Email: [email protected]

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/judith-rafferty-770a329b