Working with people in conflict, whether as a conflict management coach or a mediator, is a complex and uncertain activity. While practitioners usually follow some kind of process in their work, what they do within those processes involves a great deal of flexibility and choice. There is rarely one “right” choice for whether or how to intervene at any given stage in our interactions with clients. Often the decisions we make in the moment are based on ‘gut instinct’ or what is sometimes called ‘intuition’. Learning more about intuition, and reflecting on our own use of intuition in our practice, can greatly enhance our skills in working with clients in conflict.

What is intuition?

There are few phenomenon in the history of psychology that have so many different definitions as intuition (except perhaps attempts to define emotion)! I personally like Epstein’s (2010) simple definition:

“Intuition involves a sense of knowing without knowing how one knows, a sense of knowing based on unconscious information processing.” (Epstein, 2010).

As Lois Isenman, author of Understanding Intuition explains, intuition has recently become the focus of intense scientific study. This has resulted in a much deeper understanding of how intuition works. Isenman suggests there are three main aspects to intuition: (1) The content – this is the insight that pops into mind and we recognise as potentially important in some way; (2) Processing (sometime called “intuiting”) – this is the way in which our minds integrate information to come up with the outcome; and (3) The evaluation – this is the way in which we decide if the outcome is important, useful or true.

How does intuition work?

There are many different explanations about how the process of intuition works. Some researchers believe that it is primarily about pattern recognition. For example, when a master chess player intuitively knows the best move to make in a match, researchers such as Nobel Laureate Simon (1992) suggest that this occurs because the chess player has learnt all the different possible combinations of moves (chess playing patterns, if you like) and the player’s brain can access the appropriate one quickly and without conscious effort.

However, when working in complex situations such as with clients in conflict, it can be hard to explain our practitioner intuitions based on knowledge of pre-existing patterns in the same way as might be used in a chess match. Isenman expressed the same limitations with a pattern-focused approach when considering how research scientists use their intuition to make new discoveries that could not be explained by simple recognition of a pre-existing pattern.

Others suggest that intuition in practice settings such as medicine or mediation require a sold foundation of theoretical knowledge as well as practical experience (see for example Lang and Taylor, 2000). Dorfler and Ackermann (2012) make a distinction between intuitive judgment and intuitive insight. Whereas pattern recognition is useful for intuitive judgments, intuitive insight is when new knowledge is created and is particularly relevant in domains requiring creativity.

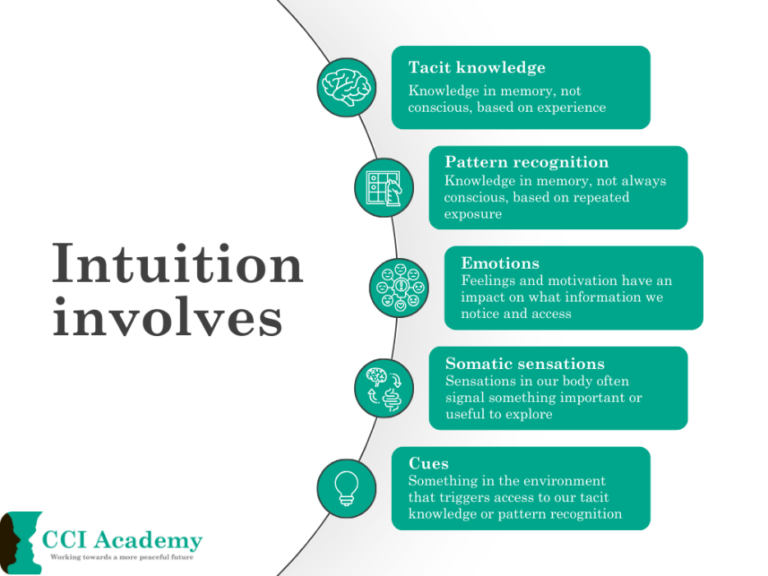

Other researchers use the broader term ‘tacit knowledge’ developed through ‘implicit learning’ as the basis of intuition. They explain that intuition occurs when our unconscious mind, stimulated by some cue in the immediate environment (which may or may not be consciously attended to), collates pre-existing information (often apparently random and unconnected), influenced by our emotions and bodily sensations, to create a new understanding or creative insight.

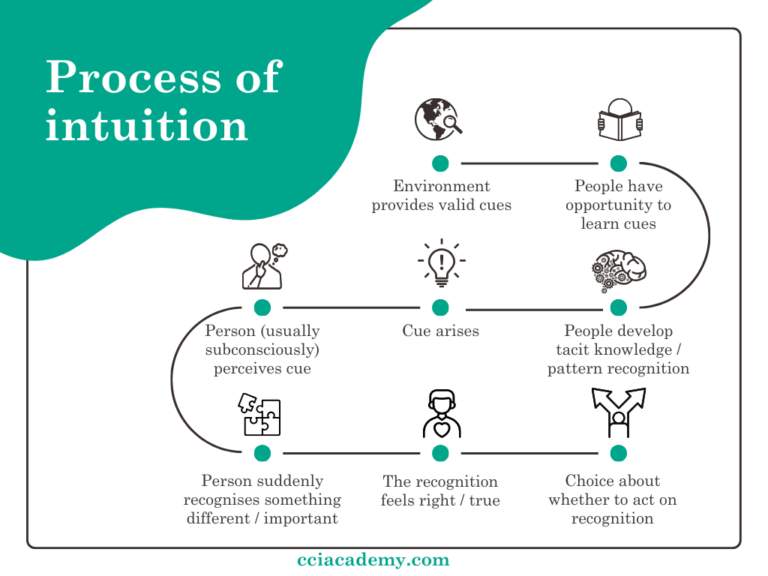

The infographic below describes how intuitions typically arise, including the pre-conditions for developing either pattern recognition or tacit knowledge to create the foundation for developing intuition in response to a later cue.

How do (should / shouldn’t) we use intuition in our practice?

It is at the point where the process flow chart ends that is the important part for our work as conflict practitioners. Intuitions are very interesting, but in a practice setting, it is what we choose to do with them that makes all the difference.

Robert Biswas-Diener, author of Positive Provocation, states:

“I have rarely come across a profession that lionizes intuition as does coaching… I hear coaches say ‘It just felt right,’ ‘It emerged in the moment,’ or other statements that prioritise intuition and hard-to-pin down insights. I’m not dismissing intuition, but I believe it is problematic in the context of professional ethics.”

Similar comments have been made in relation to mediation. Greg Rooney (2007) comments that:

“Mediators often describe how often their decision to intervene in a particular way just came to them. They experience themselves giving an instantaneous response without any apparent forethought. This experience is often referred to as having an intuition.”

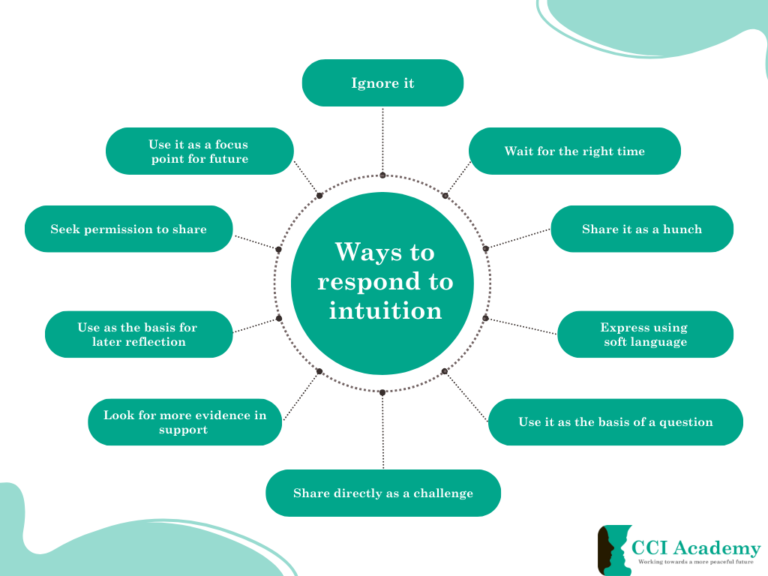

There have been a number of studies of how coaches use intuition in their work with clients (De Haan, 2008; Mavor et al, 2010; Sheldon, 2018). These studies provide useful information about when coaches typically experience intuition in their practice, what they typically do with those intuitions and why. Some of the common ways that coaches respond to their experience of an intuition during coaching are set out in the infographic below.

The research also revealed the conditions that impact on the coaches’ choices of how to respond to an intuition. These are set out in the next infographic:

One point that I found very interesting in the research is the suggestion that the coach’s level of experience seemed relevant not just because more experienced coaches have more accumulated tacit knowledge that can create the foundation for an intuition, but also because they can more automatically manage the process of coaching so that they have more mental bandwidth to pay attention to and respond to intuitions in the moment.

A common theme in the work on intuition is that it is more than just random speculation. For example, Greg Rooney, in his article on The Use of Intuition of Mediation suggests:

“If the mediator can sit with his or her own uncomfortable feelings of uncertainty and give priority to the unknown and to the immediate contact with the parties, then the feelings that arise in the mediator (their intuitive response) can produce a rich source of data. The mediator can draw on this intuitive response to decide what to do with that data. This data is immediate and specific to the parties at that particular point of time in the mediation session. It is not the product of mediator speculation even if that speculation is drawn from extensive knowledge of theory and practical experience.

What can coaches and mediators do to better use their intuition?

If coaches and mediators do act on mere speculation rather than informed and skilled intuition, there can be significant risks. Here are some tips to improve your recognition of, and use of, intuition, and also to make appropriate choices about how to act on your intuitions:

Learn about intuition and how it works.

Engage in honest reflection about your experiences of intuition and how you have responded to your intuitions in the past.

Increase your awareness of the range of cues that are likely to prompt an intuition.

Develop your comfort levels with uncertainty.

Increase your range of possible responses to intuition in your practice.

Be aware of the conditions that might impact on which response you should choose.

How can I learn more and develop better recognition of and responses to intuition?

Keep an eye out for our forthcoming webinar on using intuition in conflict resolution. In that webinar you will explore intuition more deeply, look at various case studies involving intuition, examine some of the problems and challenges in harnessing one’s intuition, and identify what is required to become an intuitively skilled practitioner. To express your interest in attending that webinar, please click here.

Robert Biswas-Diener (2023) Positive Provocation.

Lois Isenman (2018) Understanding intuition: a journey in and out of science.

Claire Sheldon (2018) Trust your gut, listen to reason: How experienced coaches work with intuition in their practice. International Coaching Psychology Review 13(1)6-20.

Dörfler, V., & Ackermann, F. (2012). Understanding intuition: The case for two forms of intuition. Management Learning, 43(5), 545–564

Seymour Epstein (2010) Demystifying intuition: What it is, what it does, and how it does it. Psychological Inquiry 21:295-312.

Penny Mavor, et al (2010) Teaching and learning intuition. Journal of European Industrial Training 34(8-9) 822-838.

Erik de Haan (2008) ”I struggle and emerge”: critical moments of experienced coaches.

Greg Rooney (2007) The use of intuition in mediation. Conflict Resolution Quarterly 25(2).

Lang, D. L. and Taylor, A. (2000) The Making of a Mediator, Developing Artistry in Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publications.

Simon, H. A. (1992). What is an explanation of behavior? Psychological Science, 3, 150 –161.