Many of the challenges that arise when neurodiverse and neurotypical people are involved in conflict are due to each person’s different way of experiencing, expressing and regulating emotions, and also the neurotypical assumptions on which many of our conflict resolution processes are based. With greater understanding and flexible approaches in the way we support diverse people in conflict and help them to work with their own and others’ emotions, many of these challenges become manageable and create opportunities for a deeper understanding of one another. Having a good understanding of the broad range of emotional diversity between any two individuals, wherever they fall on that continuum, and different strategies to work with different emotional profiles, can significantly enhance the way we work with neurodiverse clients in conflict situations, when emotions are likely to be heightened.

While there are clinical boundaries that define people as neurodiverse according to certain criteria (e.g. in the DSM-5), there are not two distinct categories of people (those who are neurotypical and those who are neurodiverse). Rather, there is great diversity within those who fall outside the DSM-5 criteria and those who are within those various diagnoses. There may be significant differences between two people who are broadly classified as ‘neurotypical’ as well as significant differences between two people who are broadly classified as ‘neurodiverse”.

Myths about neurodiversity and emotions

In the past it was thought that neurodivergent people (especially those on the autism spectrum) did not experience emotions, or could not understand other’s experience of emotions. However, recent research suggests that neurodiverse people simply use different mechanisms to make sense of their emotional experiences, to manage emotional dysregulation, and to express their emotions. They are also able to understand others’ emotions and feel empathy. They just do this in different ways from those who are considered neurotypical.

Much of the social challenges for neurodiverse people are due to their neurotypical peers not understanding the way the neurodiverse person is behaving, and vice versa. Autistic scholar Damian Milton describes this as the “double empathy problem” in which two individuals experience and express their emotions in different ways, and neither understands the other.

Unpacking different components of emotions

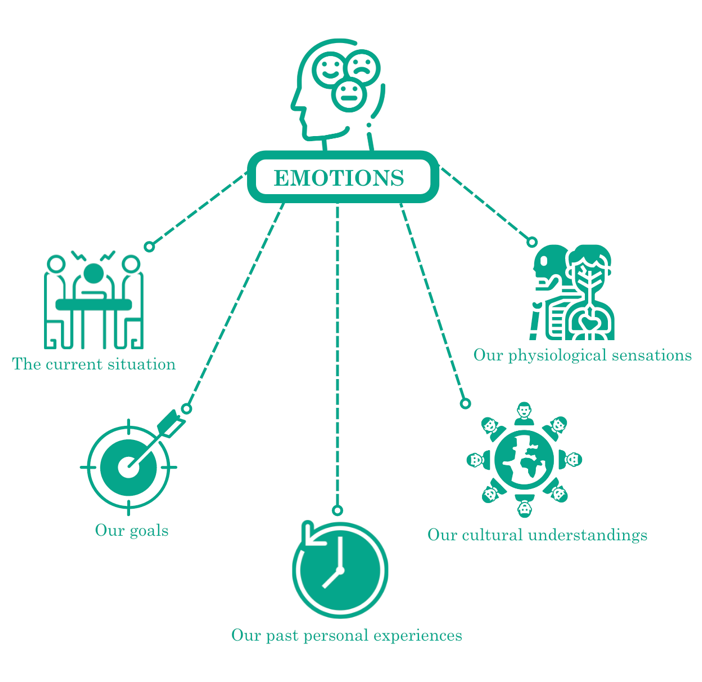

All conflict involves emotion, whether overtly expressed or not. All people, whether neurotypical or neurodiverse, experience, regulate and express emotions in varying ways depending on their past experiences and the present circumstances. In order to understand this better, it can be helpful to think about three primary components of emotion: (1) our experience of emotion (constructed by reference to our physiological experience, and also our goals, our past experiences and the current situation); (2) how we try to regulate our emotional experience; and (3) our emotional expression (how we may deliberately or unintentionally display our emotions to others using verbal or non verbal behaviours). There is also a secondary component of emotions, which is (4) emotional reflection (how we think and feel about our emotions). Each of these elements can be different across the broad range of neurotypical and neurodiverse individuals.

(1) Emotional experience

Everyone experiences emotions differently, based on a range of factors, and there is great diversity across all human beings, whether classified as neurotypical or neurodiverse.

Lisa Feldman Barrett explains that emotions come from our brain processing our bodily sensations, in relation to what is going on around us in the world, and our past experiences and expectations.

Everyone has different physiological experiences of emotions, and this can vary greatly on the continuum from neurotypical to neurodiversity. Some people are more sensitive to physiological sensations, others are less likely to connect those sensations to an experience of emotion. We all have different arousal thresholds (the point at which a physiological sensation has a positive or negative impact on us) and we all have different reaction times once we notice a physiological sensation and recognise it as emotionally relevant.

We all come with different cultural understandings about what kinds of emotional experiences are recognised, which are typical of what situation, and how they should be expressed in a socially acceptable way. There can be significant differences in understanding and expectations along the continuum from neurotypical to neurodiversity, and this can create miscommunication and misunderstanding.

Similarly, everyone has unique past experiences, and these can be very different for neurodiverse individuals as their experiences are likely to be quite varied. For example, a neurodiverse person who has faced challenges in the past trying to assimilate to neurotypical expectations may make that person highly sensitive to others misinterpreting their behaviour.

In any situation, people will be trying to achieve different things moment by moment. One person may be trying to express their anger, another might be trying to understand what’s going on, another may be trying to remain safe and in control of the situation. These different goals will have an impact on everyone’s emotional state in different ways.

Finally, the current situation, and how we interpret it, impacts on our emotions. People on the continuum from neurotypical to neurodiverse are all likely to perceive and interpret the situation differently for many reasons.

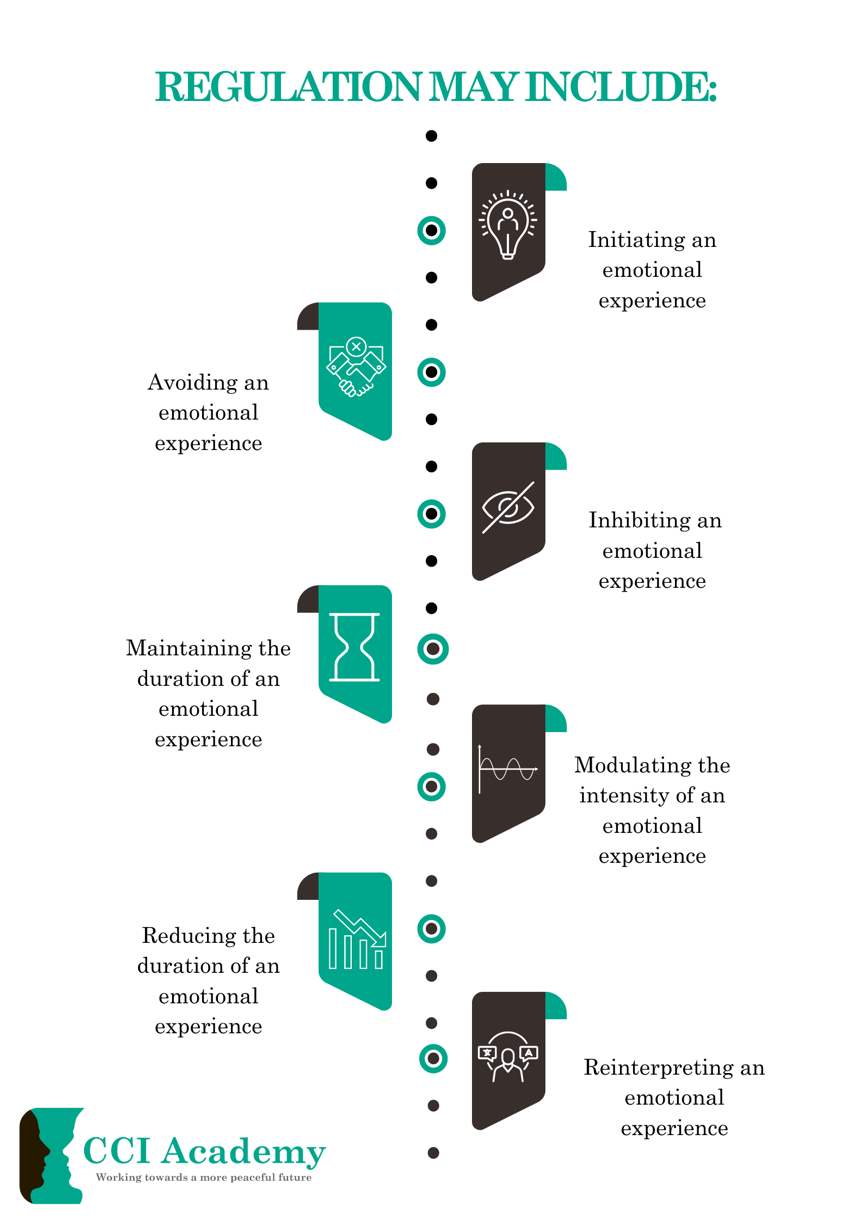

(2) Emotional regulation

There is a broad spectrum of emotional regulation abilities across individuals in different contexts. Everyone has trouble regulating their emotions in certain circumstances. We also all use different strategies to regulate our emotions. What might be considered an adaptive emotional regulation strategy for one individual may be maladaptive for another individual. Some regulation strategies may be uncomfortable for others who do not understand what is happening. For example, some people with autism engage in repetitive behaviours such as hand flapping, finger mannerisms and full-body rocking (known as “stimming”) as a strategy to regulate their emotions, but this can sometimes be disconcerting for others or seen as inappropriate in the social context. This kind of lack of understanding and acceptance may be a substantial barrier preventing neurodiverse individuals from engaging in their own positive emotion regulation strategies when needed.

(3) Emotional expression

Emotional expression can be a challenge for everyone at certain times. Some people have the added challenge of experiencing alexithymia (an inability to express one’s emotions or describe them in words). About 10% of the general population have this trait, and it is also commonly experienced by people diagnosed with autism. As well as challenges in recognising and expressing one’s own emotions, alexithymia can also create challenges in understanding and describing the emotions of others.

Everyone makes conscious choices about whether to express their emotions and which they are comfortable sharing. There are a broad range of reasons why a person may choose not to express their emotions, including feeling shame or fear that they will receive a negative response from others, that they will not be able to contain their emotional expression, or that it may damage relationships. For neurodiverse individuals who have had negative responses to their attempts at emotional expression in the past, this may be a frequently used strategy.

Whether and how we express our emotions depends on:

It’s important for practitioners to keep in mind that how a person is behaving may not provide a clear signal of their emotional experience. For example, a person may appear outwardly calm or disengaged, but internally be experiencing very strong emotions, including thought processes and high physiological arousal. This kind of masking or camouflaging of emotions can be useful in situations in which expression would be socially inappropriate, but can also lead to problems such as an unexpected huge emotional blow up as well as longer term negative psychological consequences such as increased anxiety or depression.

(4) Emotional reflection

Emotional reflection involves thoughts about one’s emotional experience, regulation and/or expression. How we feel about the emotions we experience is known as meta-emotion. For example, we may feel ashamed that we are so angry, or embarrassed that we got so upset that we burst into tears. The way we think and feel about our emotions involves our personal beliefs and values, our past experiences, and our social context. It can sometimes heighten distress (e.g. if we interpret our expression of anger as dangerous, we may feel anxious; if we see our fear as cowardly, we may feel shame). It can also diminish distress, such as when we accept our feelings of sadness as understandable and tolerable. Many neurodiverse people wonder if their feelings are ok to have, or worry that their emotional response is not appropriate.

Recognising and understanding others’ emotions

The problems that give rise to how a neurodiverse individual understands another’s experience and expression of emotion depends on the level of difference between each person. For example, autistic people usually don’t have problems understanding each other’s emotional experience and expression. However, for a neurodiverse individual, understanding a neurotypical person’s way of experiencing and expressing emotion may be a challenge. The same is true the other way around. For a neurotypical person, understanding a neurodiverse person’s experience and expression of emotion can be a challenge. However, the fact that it might be a challenge does not mean that it’s impossible. It just takes a little bit of an open mind and a willingness to learn. And it’s important to emphasise that it’s not the neurodiverse individual’s responsibility to try to assimilate to neurotypical assumptions about how things should be done. We all need to take responsibility to adapt so we can promote effective communication and understanding between people who are different from each other.

Conclusion

As practitioners, we must remember that the way we experience, regulate and express our emotions is not necessarily how others experience, regulate and express their emotions. However, this difference is not based on any deficiency or problem; rather, it’s simply natural variation that we can be curious about and learn to engage with in a way that supports connection and understanding. As practitioners, we have an important role to support every individual to work with their emotions in a way that is meaningful for them in the particular situation, and to help people who experience and express emotions in different ways to understand each other better.

Neurodiverse individuals may not disclose their neuro-status. However, if we create an environment of trust and provide opportunities for people to share with us their communication and support preferences, they may feel comfortable to do so. For example, you may be able to include a question in an intake form or conversation asking your clients how you can best support them to manage their emotions, process information and/or communicate best with others (perhaps providing a few generic examples as prompts).

As practitioners, we need to be curious about our clients’ individual experiences of emotion, and to engage with them to mutually identify how best to support their constructive engagement in conflict by accommodating their emotional needs. Practitioners can sometimes be very helpful in ‘translating’ different emotional experiences and expressions so that those who experience things differently can understand and learn from one another.

Want to know more? Register for our webinar on Neurodiversity and Conflict scheduled for 23 August 2023 here.

Some useful references for further reading

Bradley, Onovbiona, Del Rosario and Quetsch (2022) Current knowledge of emotion regulation: the autistic experience. Chapter 3 in New Insights into Emotional Intelligence

Niyathi Sulkunte, Different expressions of emotion: Neurodiversity: Communication, emotions, psychology, the mind and body.

https://adaptiveedgecoaching.com/different-expressions-of-emotion-neurodiversity/

Jessie Poquérusse, Luigi Pastore, Sara Dellantonio and Gianluca Esposito (2018) Alexithymia and autism spectrum disorder: A complex relationship. Frontiers in Psychology 9: article 1196.

Erin M. Richard (2023) Conceptualizing neurodiversity as individual differences in self-regulation. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 16: 74-76.