I’m sure you’ve all heard of the concept of the amygdala hijack. You’ve probably even used it as an explanation for why we sometimes do crazy things in the heat of the moment. Maybe you (or your clients) have even used it as an excuse for bad behaviour!

The problem is that while the concept seems intuitively useful, and is widely referred to in popular culture, it’s actually a myth and not based in any scientific evidence! Lisa Feldman Barrett includes the amygdala hijack as one of the three myths about the brain that deserve to die.

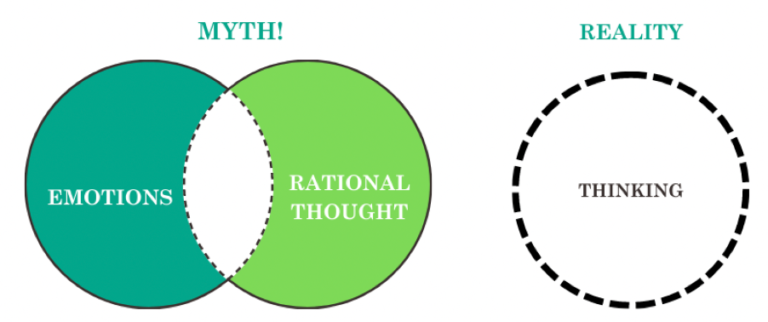

There are two main problems with the concept. First, it assumes that amygdala is the root of fear; and secondly, it assumes that there is a cognitive part of our brain (the pre-frontal cortex) that controls the emotional part (including the amygdala). As it turns out, neither of these things is true!

The amygdala is not necessarily connected with fear

Lisa Feldman Barrett’s research has shown that the amygdala turns out to be mainly useful when a person perceives an unusual face or facial expression (which is sometimes important in fear, but not always).

Her brain imaging studies have also shown that fear can exist independently of any amygdala activity.

The amygdala does function to signal that certain chemicals in the brain and hormones in the body should be secreted. This alerts the organism that something important is happening. But that important thing is not necessarily fear – it could be any thing for which a helpful response would be an energised and alert body and mind – but especially when facing uncertainty or ambiguity.

The amygdala does sometimes become activated in fear, but not always. Some studies suggest that it is activated in between 25-40% of instances of fear.

The amygdala is also routinely activated during emotions such as anger, disgust, sadness, and happiness. Amygdala activity also increases during events such as feeling pain, learning something new, meeting new people, making decisions, remembering the past, imagining the future, feeling uncertainty, eating, drinking, smelling, using language, receiving rewards, having social interactions, and regulating your body’s internal systems.

“Overall, the amygdala may be important for emotion (and dozens of other phenomena), but it is neither necessary nor sufficient for emotion.” Lisa Feldman Barrett.

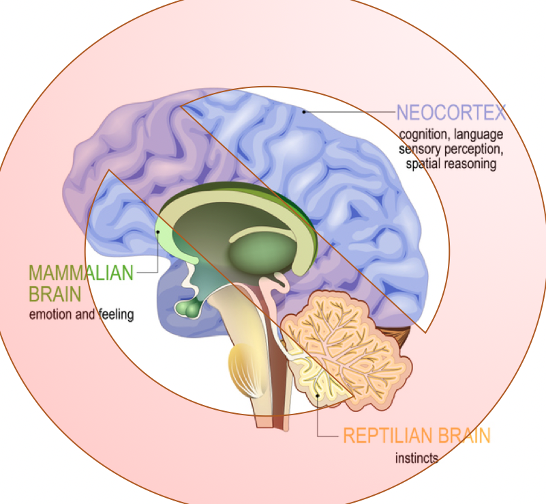

The brain isn’t divided into an “emotional” part and a “cognitive” part.

Other research demonstrates that in any emotion, many different parts of the brain are activated – there’s no “emotional” part and no “cognitive control” part.

The prefrontal cortex does not house cognition. Rather emotion and cognition are whole-brain constructions that cannot regulate each other.

So how did this idea of the amygdala hijack become so prevalent in popular culture?

The term is thought to have been coined by Daniel Goleman in his book Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. However, Goleman didn’t actually use that term at all, he referred to an “emotional hijack”. However, in his book, Goleman refers to the work of Joseph LeDoux, who was one of the only amygdala reseachers at the time, and the terms became linked. Subsequently, LeDoux himself has distanced himself from the concept of amygdala hijack.

The concept of an emotional hijack isn’t any more scientific!

Even if we take the amygdala out of the equation, and go back to Goleman’s original term of “emotional hijack”, it’s important to understand that this isn’t a concept founded in science either. Nicole Gravagna calls “the emotional hijack” a great example of a non-technical factoid – something that sounds like science but is actually just a term that describes a human experience (rather than provides a scientific explanation for it).

“Emotional hijack is … an elegant, descriptive, non-technical term. It was never meant to describe how the brain works. It was meant to help people understand complex human experiences… “If you asked a neuroscientist to judge whether an emotional hijack is a real thing, they may shrug and say, “I guess I feel hijacked by my emotions sometimes.” Nicole Gravagna

An emotional hijack is a comforting concept – we can blame that nasty amygdala for making us all emotional and behaving irrationally – but it’s by no means that simple! There is a much more complicated process involved in the release of hormones (and some of that involves our ‘cognitive’ appraisal of the situation we are responding to).

What does this all mean?

Firstly, we probably have more control over our responses, even when we are feeling flooded, than we realise.

However, our level of control depends a great deal on our personal emotional profile – some people are more likely to become flooded due to their past emotional experiences and habits. Our level of control also depends a great deal on the context – while we might “lash out” when feeling flooded in some situations, in others we will be able to control our responses. If we have a high level of emotional agility, we will be able to identify the kinds of hooks that tend to lead us into that flooded feeling, and we will also be able to put some regulation strategies in place when we are likely to be exposed to those hooks. We can also work on our general predisposition to flooding by practices such as mindfulness and reflection (or perhaps more supported interventions such as counselling if we are frequently hooked into a feeling of being flooded, or our responses to that experience are extreme).

One of the best ways to be able to improve your capacity to work with your emotions (rather than feeling like they are controlling you!) is to learn more about how emotions work, reflect on your personal experiences with emotion, and to practice new strategies. You can do all of these things in our online course Working With Emotions in Conflict! The course will help individuals to work with their own emotions, and practitioners to work with both their own and clients’ emotions. Find out more here: https://conflictmanagementacademy.com/wwe-online/

Additional reading

Lisa Feldman Barrett (2017) How emotions are made: the secret life of the brain.

Lisa Feldman Barrett (2017) Three Myths About the Brain (That Deserve to Die)

NBC News, April 14, 2017

https://www.nbcnews.com/mach/science/three-myths-about-brain-deserve-die-n744956

Nicole Gravagna (2019) Neuroscience: Out of Pandora’s Box and Into the Boardroom

http://www.theneuroethicsblog.com/2019/07/neuroscience-out-of-pandoras-box-and.html

Sarah McKay (2020) Rethinking the reptilian brain.

24 June 2020.

https://drsarahmckay.com/rethinking-the-reptilian-brain/

Joseph E. LeDoux (2015) The amygdala is not the brain’s fear centre: separating findings from conclusions. 10 August 2015.