What is trust?

The word trust can be used as a noun (something you have) or a verb (something you do).

As a noun, trust can be defined as “assured reliance on the character, ability, strength or truth of someone or something” (Merriam-Webster)

As a verb, trust can be defined as a belief that “someone is good and honest and will not harm you, or that something is safe and reliable” (Cambridge English dictionary).

For our purposes, I like Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman’s (1995) simple definition: “Trust is being vulnerable within a social interaction”.

Researchers from many fields (including economics, management, anthropology, philosophy, biology, sociology and psychology) have investigated trust. There’s even an entire journal on trust research.

Some elements of trust proposed by various researchers include:

Reliability / integrity / accountability / confidentiality

Appropriate management of emotions (your own and others’)

Openness, honesty and transparency

Good intentions / care / benevolence

Competence / ability

Safety – physical and psychological

Respect / non-judgment

Empathy

Self-knowledge is also required for trustworthiness. This reinforces that reflective practice and supervision is an essential part of being a trustworthy practitioner.

“Being honest with ourselves about what we know, and what we don’t, about our capacities, skills, and weaknesses, is a pre-requisite for being trustworthy to other people… Trustworthy people are often good at assessing their own skills, knowledge, and limitations, so that they know when to offer help or advice and when to stand back. Sometimes, the trustworthy option is to say ‘I don’t know’, or ‘I’m afraid I can’t do that for you’, even when we know this will disappoint. To be trustworthy to others, we need to be honest with ourselves about what we can realistically manage, and where our weaknesses lie. Over-optimism about our own talents gives rise to one form of untrustworthiness.” Katherine Hawley (2012)

Context is also important in trust. For example, the kind of relationship the parties are in or considering. Trust may look different in a romantic relationship compared to a professional relationship between a client and a practitioner. The availability of external standards or codes of conduct may also be relevant (for example, the ICF Core Competencies or the NMAS Practice Standards both provide professional requirements that may contribute to trust in practitioners regulated by those standards). Whether a client is working with a practitioner voluntarily or whether their participation is mandatory is also likely to influence trust.

Why do we need it?

“Imagine you are a coaching client and after your first session … you have concerns about the coach’s competence, you wonder if the coach is being honest with you, and you do not think the coach cares about you. Would you feel that you could open yourself up to the coach and talk about your dreams, goals, and desires?” Schiemann et al (2019)

The key reason that a client working with a conflict practitioner needs to trust the practitioner is that successful engagement in conflict (whether that is in coaching or in a mediation) requires a level of vulnerability and risk.

Trust in the practitioner helps enhance communication between practitioner and client. It provides psychological safety so that the client can feel comfortable sharing information and openly expressing their emotions. The ICF Core Competencies expressly include cultivating trust and safety to allow the clients to share freely (core competency 4). Australian researcher Susan Douglas suggests that trust is inherently related to ethical practice as a mediator.

Trust in the practitioner also helps clients to put down their defensive shields and to acknowledge their contributions and choices (both past and future). It also helps clients to embrace uncertainty, to be willing to take risks and try something different.

How do practitioners build clients’ trust?

Initial trust

Practitioners who are accredited by a professional standards body (such as the ICF or the NMAS) may have a base level of trust established by the system of credentials, qualifications and monitoring in which they are embedded (assuming the client knows about and understands what these bodies represent). Practitioners who are trained and certified, and who practice using a reputable process or model (e.g. facilitative or transformative mediation, or REAL Conflict Coaching™) will also gain trust associated with that way of practising. Practitioners who have evidence of continuing professional education (e.g. university qualifications or other relevant course completions) will also typically be trusted to be knowledgeable and competent. Practitioners may also demonstrate trustworthiness by their inclusion on relevant panels or their history of work with reputable organisations, as this implies that others trust them. Similarly, clients are likely to trust practitioners who have been recommended to them by someone whose opinion they respect. Practitioners also build trust by the way they present themselves and their services (for example, on their website or social media).

Developing trust during service provision

Once the client begins to engage directly with the practitioner, trust can develop as the practitioner demonstrates their competence, but trust is also heavily dependent on the practitioner’s personal attributes. The practitioner needs to be able to demonstrate reliability, integrity, accountability and confidentiality. They need to be able to manage their own and clients’ emotions in an effective and respectful way. They must be able to be open, honest and transparent, and show that they have good intentions towards the client and that they care about the client’s needs. They need to ensure the client’s physical and psychological safety and to consistently interact in a respectful, empathetic, and non-judgmental manner.

Some interesting research on how coaches typically attempt to build trust with their clients found that inexperienced coaches focused their trust-building behaviour on communicating their ability. In contrast, the experienced coaches focused their trust-building behaviour on communicating benevolence.

Research into how mediators build trust identified five key factors that determined whether a client trusted their practitioner: degree of mastery over the process, explanation of the process, warmth and consideration, chemistry with the parties, and lack of bias toward either party.

Trust needs to go both ways

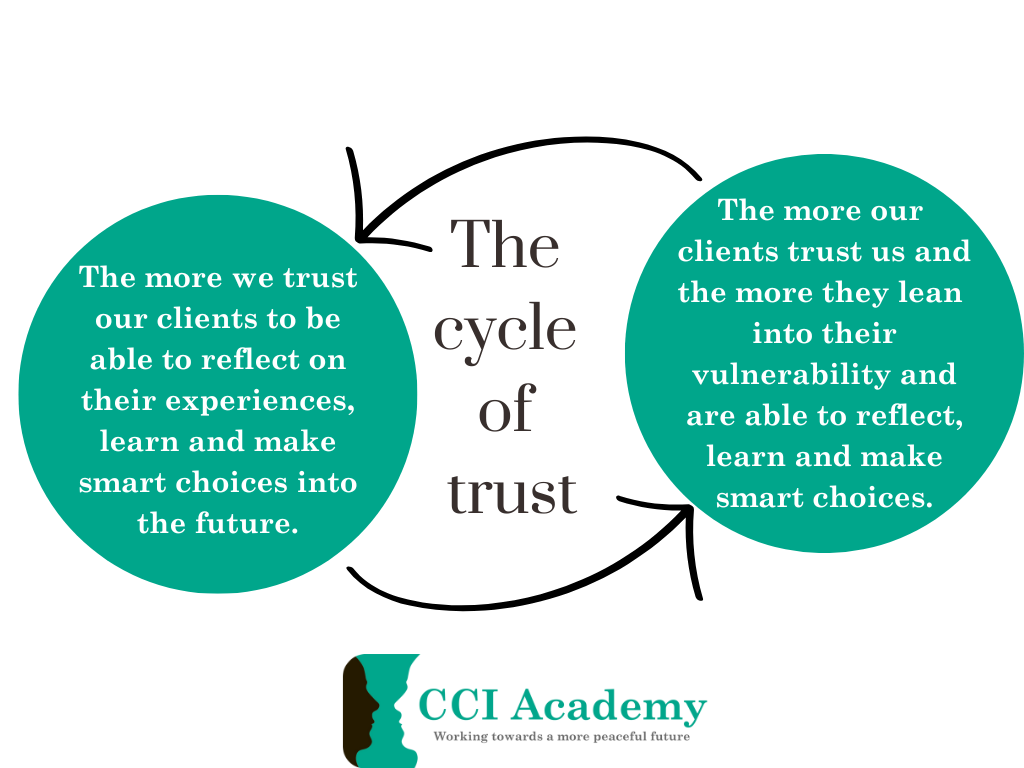

We talk a lot about the importance of the client trusting the practitioner, but it’s equally important that the practitioner trust the client!

We need to trust that our clients have the resources that they need to make their own choices. We need to trust that our clients know what’s best for themselves. When we do not trust our clients, we are in fact insulting them. When we lack trust in someone, we form negative expectations about what others will do and say, about their motives, capacities, and expertise. This can create self-fulfilling prophecies.

How do you demonstrate your trustworthiness to prospective clients?

How do you build trust with your clients?

How do you demonstrate trustworthiness relating to each of the elements of trust described above?

Trust

Dr Henry Cloud (2023) Trust.

Charles Feltman (2021) The Thin Book of Trust, 2nd ed.

Katherine Hawley (2012). Trust: a very short introduction

Stephen M. R. Covey (2022) Trust and Inspire.

Ken Rotenberg (2018). The psychology of trust

Harvard Business Review (2023). HBR’s 10 Must Reads: On Trust

O’Neill, O. (2013). How to trust intelligently. TEDBlog. https://blog.ted.com/how-to-trust-intelligently (accessed 16 May 2022).

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734

Brene Brown BRAVING Inventory https://brenebrown.com/resources/the-braving-inventory/

Trust in coaching

Jovana Markovic, Jean McAtavey, Priva Fischweicher (2014) An integrative trust model in the coaching context. American Journal of Management 14(1-2) 102-110.

Wendy Smith et al. (eds.) (2023). The Ethical Coaches’ Handbook

Alvey, S. & Barclay, K. (2007). The characteristics of dyadic trust in executive coaching. Journal of Leadership Studies, 1(1), 18–27.

Sandra Schiemann et al (2019) Trust me, I am a caring coach: The benefits of establishing trustworthiness during coaching by communicating benevolence. Journal of Trust Research 9(2):164-184.

Trust in mediation

Michael Blackstock (2001) Where is the trust: Using trust-based mediation for first nations dispute resolution. Conflict Resolution Quarterly 19(1):9-30.

Salem, Richard. “Trust in Mediation.” Beyond Intractability. Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: July 2003 <http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/trust-mediation>.

Susan Douglas (2017) Ethics in mediation: Centralising relationships of trust. Ethics in Alternative Dispute Resolution, Law in Context 35(1): 44-63

Jean Poitras (2013) The strategic use of caucus to facilitate parties’ trust in mediators. International Journal of Conflict Management 24(1):23-39.

Jean Poitras (2009) What makes parties trust mediators? Negotiation Journal, July 2009, 307-325